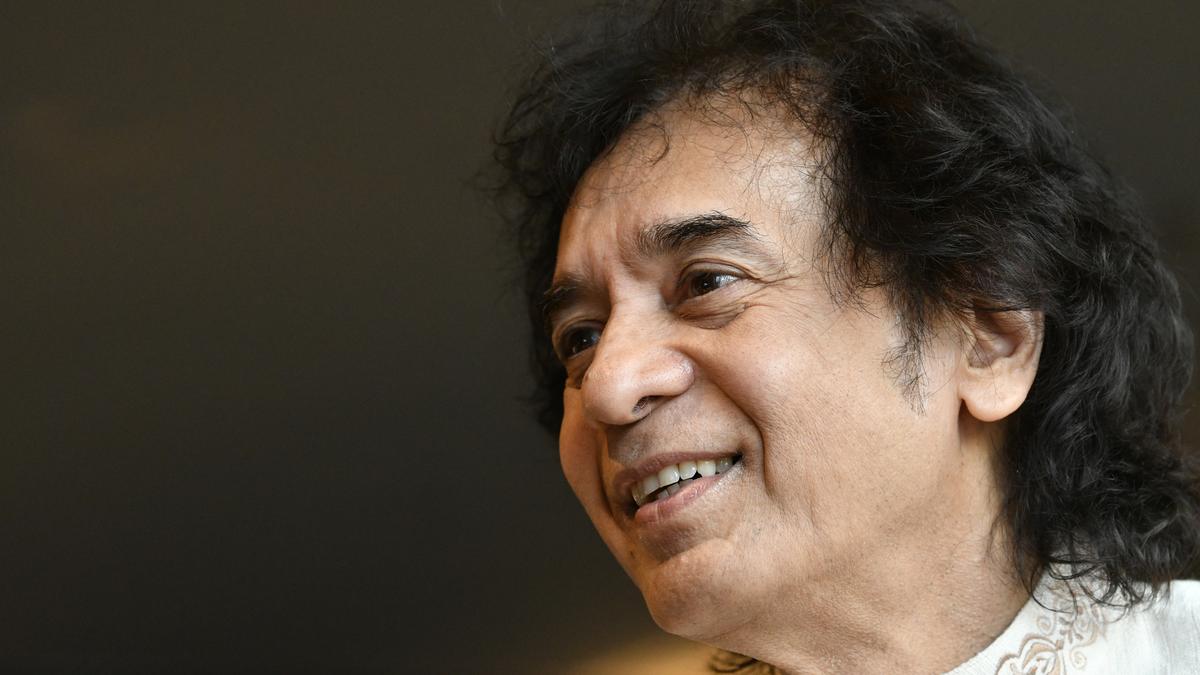

Tabla player Zakir Hussain in conversation with The Hindu in 2023. Photo courtesy: K. Murali Kumar

Ustad Zakir Hussain (1951-2024), one of the greatest global ambassadors of Indian classical music, passed away on Monday (December 16, 2024) in San Francisco, California after a brief illness that left the tabla silent. A maestro who transformed the humble instrument into a powerful voice for universal peace and humanity, Hussain’s incredible speed, dexterity and creativity mesmerized audiences of all cultures.

Having grown up singing praises of Mother Saraswati, verses from the Holy Quran and hymns from the Bible as daily rituals, the syncretic soul of India resonated through Hussain’s rhythmic art. With a penchant for crafting stories out of percussive sounds, his conversational music resonated with a spark of spontaneity. Natural flow defined his music and personality. The Padma Vibhushan will impress purists, thrill fusion lovers and indulge Bollywood music fans alike in their creative space. At the peak of his creative genius, he won three Grammys in one night this February.

Follow: Live updates of Zakir Hussain’s death – December 16, 2024

Like his carefully designed free-flowing style, the versatile artist will execute intricate rhythms, complex patterns and subtle dynamics and then move on to items like traffic signals and deer movements, without putting the music in brackets. In tune with technology, over the years, he experimented with frequencies to bring out the subtle shades of the instrument and established that the tabla is not just a rhythmic instrument but also a melodic instrument. He emerged on the scene along with eminent tabla artists like Anindo Chatterjee, Shafaat Ahmed Khan, Kumar Bose and Swapan Choudhary, but Hussain’s role in popularizing tabla and providing it a global platform is unique.

Born to Ustad Alla Rakha, the renowned accompanist of Pandit Ravi Shankar, who is credited with taking tabla to foreign shores, tabla chose Hussain. He grew up in Mumbai in an environment where his father believed that every instrument had its own soul. Husain became friends with the tabla at the age of three, and by the time he reached adolescence, the instrument had become the basis of his life and perhaps an extension of his personality. After watching him play, no one could see tabla playing as a chore in classical music.

His other two brothers, Taufiq and Fazal, are also renowned percussionists, but Hussain took his father’s legacy to the next level by adding a touch of showmanship and expanding the wealth he inherited from the Punjab gharana. A keen learner and listener, Hussain was like a sensitive satellite in orbit as an accompanist, shining like a star in his solos, and reserving a meteor’s adventurous streak for creating fusion music.

Hussain, a child prodigy who made his first professional appearance at the age of 12, was not guided by his teacher-father. Rooted in Indian tradition, they were allowed to grow wings and explore new shores. His day would begin with devotional music invoking Hindu deities, after which he would recite Quranic verses at the neighboring madrassa before attending morning prayers at the convent school. By the age of 19, Hussain taught at the University of Washington before enrolling at Ustad Ali Akbar Khan’s College of Music in San Francisco, where he met his classmate Antonia Minnecola.

Also read: Zakir Hussain: ‘Student should motivate teacher to teach’

Power

Another chance meeting in New York led to his lifelong association with the celebrated English guitarist John McLaughlin. Their friendship led to the formation of the groundbreaking Shakti Band in 1973, which included violinist L. Shankar and percussionist TH Vinayakram, who blended Hindustani and Carnatic classical music with Western jazz influences. This year, the band in which Hussain joined hands with a new group of distinguished musicians won the Grammy Award for Best Global Music.

Hussain’s willingness to experiment led to rewarding collaborations with Irish singer Van Morrison, American percussionist Mickey Hart, Latin jazz percussionist Giovanni Hidalgo and Grateful Dread lead singer and guitarist Jerry Garcia. He also joined the electronic boom of Asian underground music in the 1990s but retained the natural acoustic quality of the tabla. He shared a special bond with santoor maestro Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma, flautist Hari Prasad Chaurasia and sarangi maestro Ustad Sultan Khan. Their Jugalbandis would start as sweet banter and then turn into meditation. Keeping pace with the next generation, last year, he composed the Triple Concerto for tabla, sitar and flute with Niladri Kumar and Rakesh Chaurasia, and his collaborations with Carnatic musicians extended to violinist Kala Ramnath and veena player Jayanti Kumaresh .

Fusion was never anything new to Hussain as he grew up hearing stories of how Amir Khusro blended the Indian traditions of Dhrupad and Haveli music with Sufi Qaul to create Khayal. As a young composer, he watched his father and colleagues contribute to Hindi film music, drawing liberally from diverse musical streams. Hussain’s association with cinema came when he played the tabla for Laxmikant Pyarelal’s debut film Parasmani. He later composed music for films like Ismail Merchant MuhafizAparna Sen’s Mr and Mrs IyerAnd Rahul Dholakia’s ParzaniaThe meaningful sound of his tabla provided layers of storytelling in international productions such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now And recently Dev Patel’s monkey Man,

Hussain was fond of acting since a young age. It is said that Dilip Kumar had recommended his name to K Asif for the role of young Salim in Mughal-e-Azam but Ustad Allah Rakha vetoed it. Later, he performed in Ismail Merchant’s Heat and Dust and Sai Paranjape’s Saaz. However, he became a household celebrity when he brought classical music into the mainstream by endorsing a tea brand in an advertisement where he played the tabla in the iconic Taj Mahal. As described in an article in The Hindu, “Wow Taj!” Combination of. The stunning young Hussain’s curly hair flying across his face as his fingers glided across the surface of his tabla – not to mention that charming smile accompanying the resonance of his playing – ensured the immortality of the brand.

Fame did not diminish his humility and age did not diminish his curiosity. For Hussain, music was an endless journey. Whenever someone tossed out the word perfection, he would say, “I didn’t play well enough to give it up.”

published – December 16, 2024 09:04 am IST