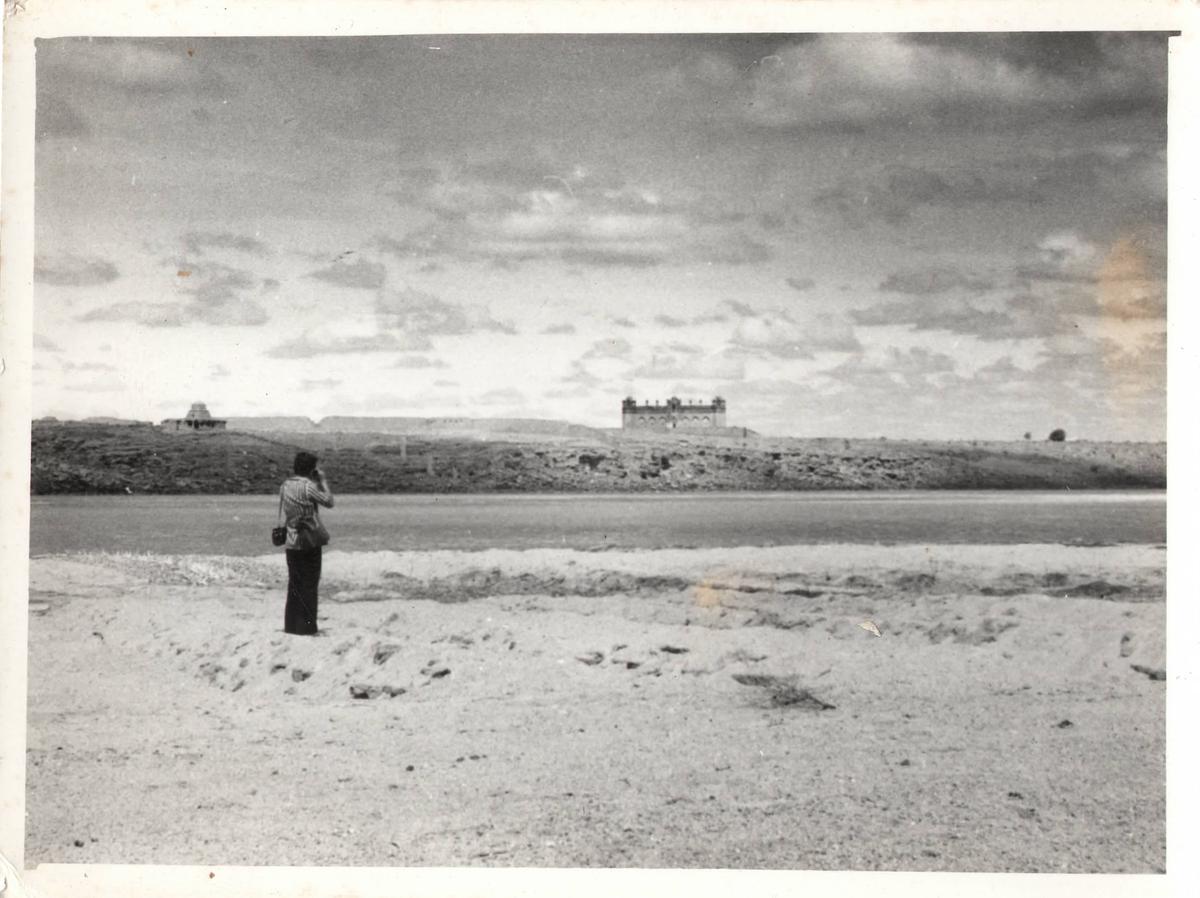

Below the plasid lake In Berlinley | Photo Credit: Leo Hugndubel

When the artist Kush Badahwar was living in Hyderabad in the early 2010s, the caretaker of his building suggested that he could be interested in seeing a neighbor’s personal collection who died. It was discovered, it was related to Radha Krishna Sarma, professor of ancient Indian history at the University of Osmania. His family was settling the remains of his educational works stored in the house. This serndipitus event took place at a time when Badahwar was thinking of various archival materials in the context of his research on the Telangana State Goods Movement on an India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) archial fellowship.

The collection had VHS tapes, notes, books and about 1,500 35-mm photograph slides. As he began to study him, he discovered several photographs of the Vidhiratha crowd of Srisailam Dam area and the famous Salve Archaeological Project. From the late 1970s to the late 80s, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) raised transplants and reconsideration of more than 100 ancient temples in Telangana that were in danger of submergence.

Further research inspired him to work for the work of New York-based humanist Vyjayant Rao, whose research focuses on the influences after dam construction-the social, cultural and economic life of the villagers who had displaced as their homes and land. The cooperation between Badwar and Rao since 2021 resulted in an artistic project, which was first painted in Chicago Architecture Bienle in 2023 Monumental returnAnd as recently Below the plasid lake The expansion of the 75th Berlinley expanded in the prestigious Forum. Now, the pair has been invited to present in the world around the summit in the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City on 27 April.

Below the plasid lake

Photo Credit: Leo Hugndubel

Forced expulsion and a visual installation

The last of the large -scale modernization projects of the Nehruvian era, Srisailam Dam was approved in 1960 and it took two decades to complete the construction. The promise of the state of development and progress demanded the sacrifice of the land and livelihood of the villagers, even resources were dedicated to saving old temples – the major importance to the narratives of nationalist history. Eventually, more than 100 villages were submerged and 1,50,000 people were displaced. But this sad story has not made an impression in the cultural memory of the country. In this context, the project of Badar and Rao is a welcome intervention that begins a new negotiation, and provokes us to revaluate the current discourses of state -led development development.

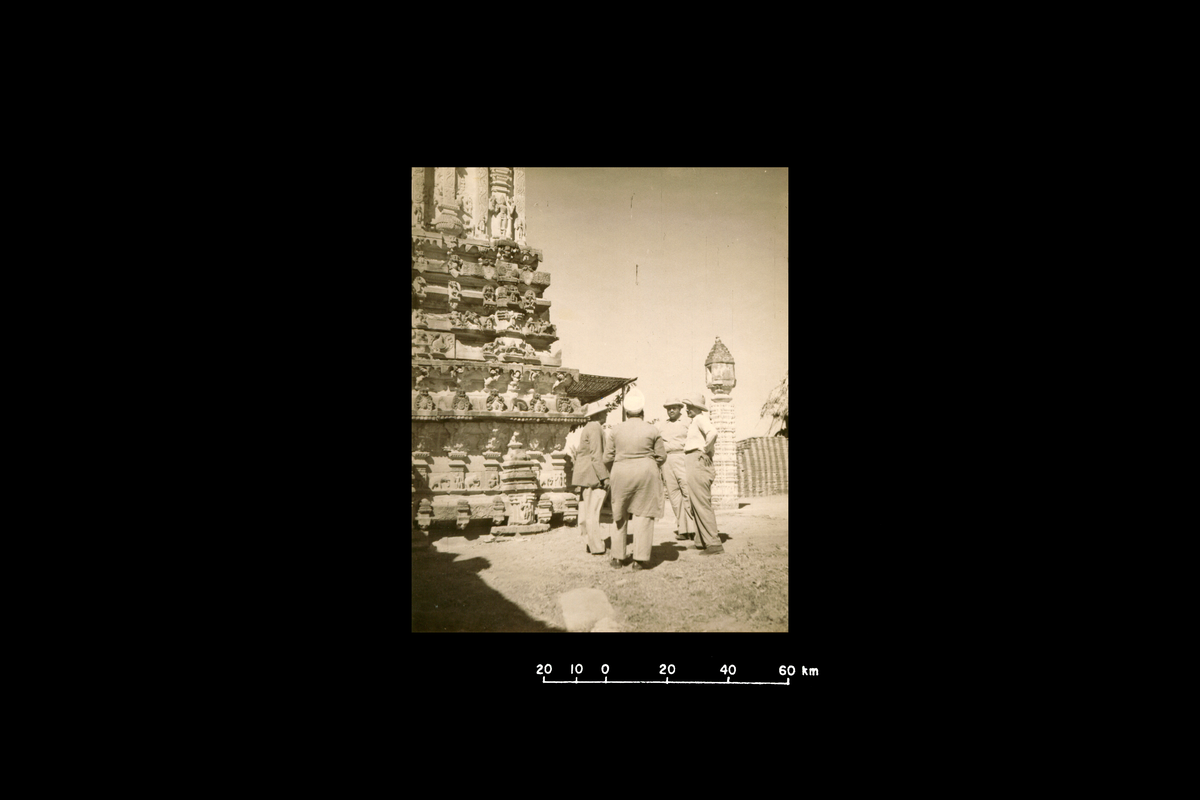

A picture from installation

I saw Below the plasid lake In Berlinley. The projection-based installation consisted of a television monitor, on which the documentary Rush was played with curated text, and images from the slides were introduced on the same screen. While the crowds are from the archives of Sarma, images are a mixture of the documents of the late professors of temples before the dam project and in the late 1990s, the Salven Archology Project, during the field research of Rao, and maps and paintings from the archives of French Institute of Pondicherry. The text on the screen is Rao’s poetic rehabilitation which is from the journey of his field notes to A. Dargah Some local women in the submerged parts of Jetprol village.

Through the superimpression of three different types of research materials, the installation urges the audience to consider the cultural, social and spatial experiences of displacement. Although it does not attempt to tell the story of displacement and the transplant of more than 100 temples linearly, the formal function of the superimpression of research materials of three generations of various subjects tells the story of various knowledge practices in the same context. As an academic with a keen interest in temple architecture, the images of Sarma focus on ancient structures and archaeological project; Rao’s text – as a researcher and anthropologist – reflects the loss of social and physical references of villagers and the loss of suspended nature of their lives, snatching the submerged parts and the remains of a new village.

A slide from installation

Three generations of research

While the viewer can experience and engage with the formal characteristics of visual installation, multi-layered premature concerns are not immediately clear-until one is already aware of the context of the Srisailam Dam project. When I ask the pair about this, Rao shared that his discovery is to find new and different ways for such stories of displacement, which should not be interpreted, but to focus on experience; She realizes that the art project provides an opportunity to go beyond the representation allowed by academic writing or activism, which has been advertised in the Sreesailum context. “We exist in relation to a network of texts and, therefore, are also limited by the material we collected,” says Burgwar.

A slide from Below the plasid lake

He explains that the journey of the project has been like a rehearsing, almost like rehearsing: it was first presented as a lecture performance on Sarma’s archives at the 2019 Flehry Festival in Canada before converting into an establishment with focus on displacement for the first time.

How are they getting closer to the MOMA event, which seems like a seminar compared to an exhibition? While Rao revealed that he is planning a lecture performance, Budwar says that he plans to be seen to be amiologically with two parallel story lines: about various knowledge production methods of three generations of researchers, and the story of the dam and then.

The summit will be livestream on YouTube on 27 April. Is through registration Momma website,

Bangalore -based writer, filmmaker and teacher Srishati Manipal teaches at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology.

Published – April 23, 2025 05:49 pm IST