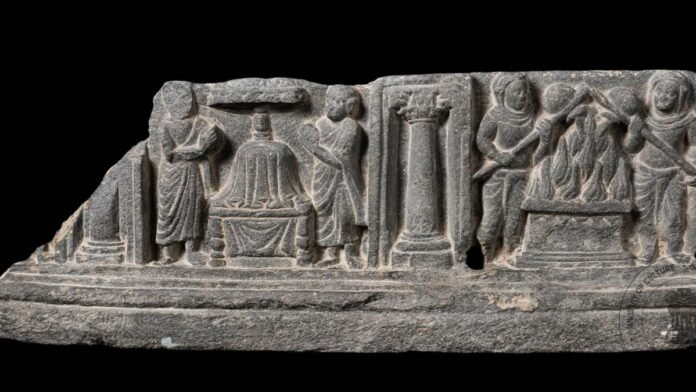

Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) has launched a bold experiment in the way history is taught and experienced. ‘Networks of the Past: A Study Gallery of India and the Ancient World’, which opened its doors today, has brought together over 300 archaeological objects from 15 Indian and international museums to argue a simple but powerful claim: ancient India was not isolated, it was a center of global exchange.

Designed as a study gallery, it includes Harappan seals and pottery, Mesopotamian cuneiform, Egyptian sculpture (even a cat mummy), Greek and Roman paintings, Chinese ceramics and jade, coins, inscriptions, and everyday objects so that students and the public can study antiquity as evidence, not myth. The timeline runs from the Indus-Sarasvati (Harappan) Civilization approximately 5,000 years ago to the Gupta era of the sixth century AD, and concludes by placing two of the great knowledge economies of the ancient world – Nalanda and Alexandria – in conversation, reminding visitors that ideas have always traveled just as fast as objects.

At a moment when historical thinking is increasingly disrupted by revisions of textbooks and shrinking space for critical inquiry, this project creates an alternative route into the past: one based on material evidence, shared human questions, and a spirit of intellectual play.

Harappan Storage Jar Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

A lyre owned by Queen Puabi of the Sumerian city of Ur. Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

“It is only when we see the Harappan civilization in the broader context of its extensive, far-reaching trade relations with Mesopotamia, do we realize the true achievement of its predecessors… India is part of a much larger story, and only from such a perspective can we see how astonishingly great has been its contribution to the world.”Jyoti RoyAssistant Director (Projects & PR), CSMVS

‘A History Beginner’s Toolkit’

Over four years, CSMVS co-curated the gallery with partner institutions including the British Museum, Staatliche Museum zu Berlin, the Benaki Museum (Athens) and others, supported by the Getty’s Sharing Collections Programme. Indian and international curators jointly selected the objects and co-wrote interpretive outlines targeted at Indian audiences.

That academic ambition is clear. CSMVS has built a neighboring learning centre, Nalanda, and incorporated the gallery into the university partnership. More than 20 institutes will prepare courses based on core subjects. Outreach through audio guides, short films, a dedicated website, and its Museum on Wheels and Trunk Museum projects (outreach programs featuring mobile museums and themed trunks filled with artifacts) promises to take curated encounters beyond the metropolitan elite and into schools across the country.

Funerary statue of a Roman boy. Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

A rhyton with a caracal cat, silver drinking vessel from the Parthian era. Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

A Dragon Pendant | Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

Importantly, many of the loans are long-term: the gallery will remain on view for three years, allowing ongoing engagement. As Assistant Curator (International Relations) Renuka Muthuswamy says, this format “acts almost as an ancient history starter toolkit for Indian students”, bringing what is often taught “in a chronologically incoherent manner” into a single, coherent experience.

The gallery is also a reformulation of the old museum grammar that placed the Mediterranean at the center of ancient world history. By foregrounding exchanges – trade networks, shared technologies, diasporic motifs – the CSMVS repositions India as both a contributor and beneficiary in the pan-continental tapestry. “Stories in museums are often presented in a linear format to an assumed ‘homogeneous’ audience,” explains Nilanjana Som, curator (arts). “But audiences are diverse, Indian audiences are even more diverse.” This matters politically and intellectually: museums in formerly colonized regions have long been arenas where authority over the past is contested. Co-operation and shared guardianship, as practiced here, are practical answers to that competition. “Looking through each other’s eyes, we see these objects in a new way,” says Thorsten Opper, chief curator of Greek and Roman sculpture at the British Museum.

A Gemini statue. Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

Statue of King Ptolemy II of Egypt. Photo Credit: Courtesy CSMVS

Test Case for Indian Museum Practice

Of course, there are limits. No matter what the gallery chooses, omissions and emphases will invite debate. Nevertheless, the scale of the project and its clearly educational purpose make it a test case for Indian museum practice: can objects provoke public reasoning rather than passive admiration? Can long loans, co-written labels and class partnerships change who gets to narrate the past?

For visitors, the immediate pleasure is fundamental: standing in front of a seal or coin and realizing a series of human choices that have spanned thousands of years. For teachers and curators, the value is structural: a model for interaction between museums, scholars, and the public. Networks of the Past does not close the book on antiquity; This opens a desktop of questions that are asked to read, teach, and debate.

The essayist-teacher writes on culture, and is the founding editor of Proseterity – a literary arts magazine.

published – December 12, 2025 06:18 pm IST