Visitors to Fort Kochi will see an unusual installation on the first floor of the Dutch Warehouse. Large brightly colored cuddly dolls are playfully placed on plush carpets. Dutch artist Afra Isma, through the installation ‘Hush’, invites viewers to join the work – sit for a while, cuddle with the dolls if necessary. It’s all about connection, she says.

The show, presented by The Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, baby teethis a two-part work – Hush and Warrior Garments – that defines Isma’s deeply political, yet emotionally charged practice.

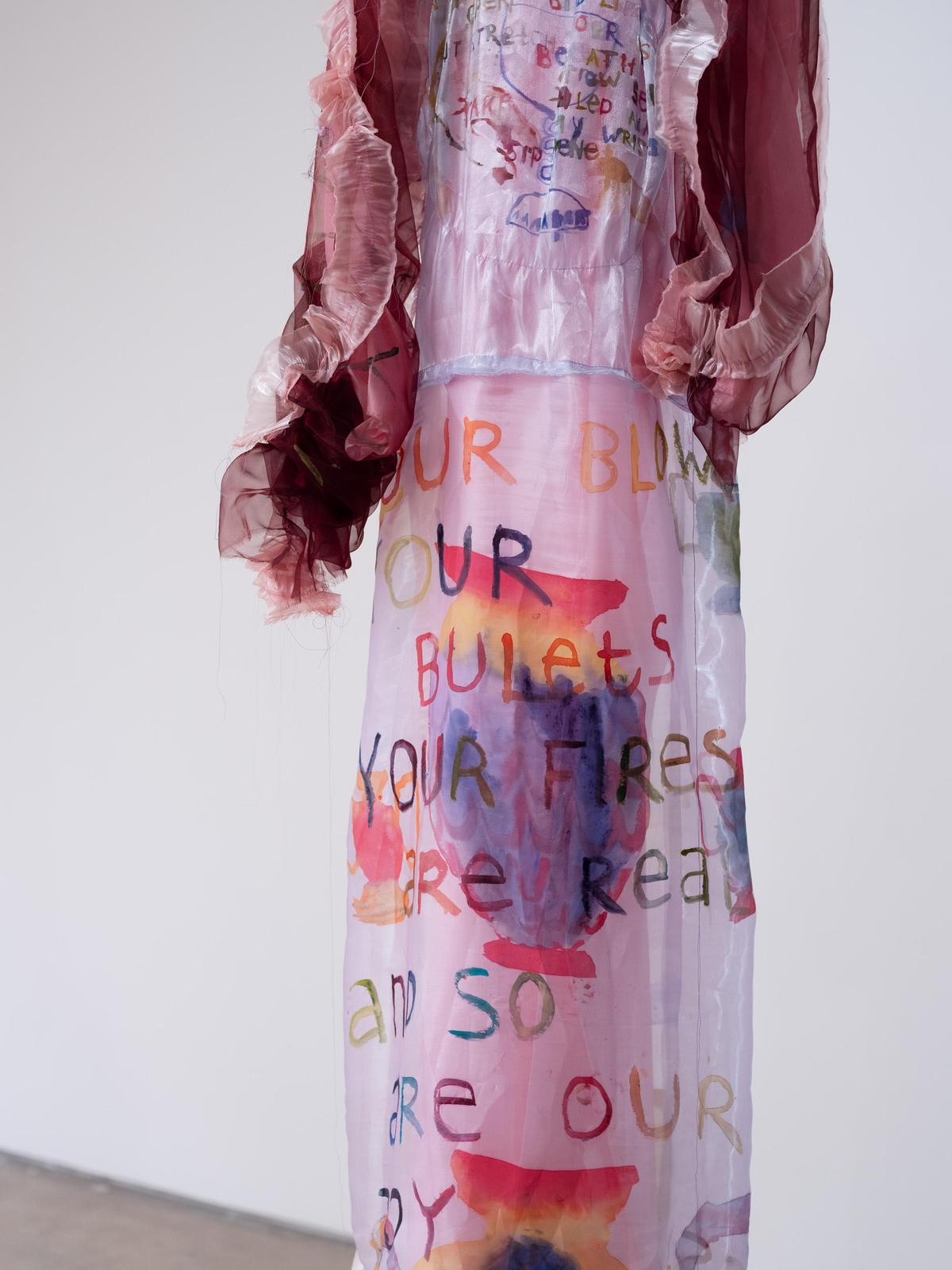

While ‘Hush’ is a mosaic of soft carpets, ceramics and textiles spread across the room’s floor in a tactile tapestry, ‘Warrior Garments’ features long robes of silk and organza with hand-painted text running through them.

Afrah Isma’s work ‘Hush’. Photo Credit: Philipp Scholz Ritterman

Nominated for the Volkskrant Visual Art Prize 2026 (a prestigious art award for artists under the age of 35 living or working in the Netherlands), 33-year-old Isma was at the forefront of the #metoo movement in the Netherlands, which sought to highlight sexual violence and exploitation in the art world.

Edited excerpts from an interview.

The installation, ‘Hush’, features comfort among large, soft creatures. Where did this idea come from?

The idea of ’Hush’ arose from the need to create a space of safety and care. At the core of the exhibition is my practice of processing personal trauma through creation, particularly trauma associated with gender-based violence and its physical consequences. The title of the piece ‘Hush’ refers to breathing which became a starting point. Breathing is both intimate and powerful: a simple, physical act that can calm the nervous system and reconnect body and mind. From there, soft, oversized creatures emerged as physical expressions of comfort, protection, and mutual support.

They are imagined companions, supernatural beings designed to hold, carry, and monitor each other, who model the kind of care that I believe is necessary for healing. The scale and finesse of the works is deliberate. By making the shapes large, soft and enveloping, the work invites visitors to slow down, take off their shoes and enter a space that does not feel threatening and eclectic. ‘Hush’ ultimately arises from a desire to transform pain into a shared, gentle environment, where vulnerability is allowed, attention is paid to the breath, and comfort becomes a collective experience rather than a solitary one.

A visitor interacts with the installation ‘Hush’ Photo Credit: Philipp Scholz Ritterman

How would you describe your artistic process?

My artistic process begins with emotion rather than form or concept. Emotions, especially those that are often considered uncomfortable, such as anger, grief, fear or ambiguity, are regarded as sources of inner strength and wisdom. I work very intuitively, allowing experiences, physical sensations, memories, conversations and active movements to gradually coalesce into images, textures and characters. Making is a way of processing: by working with my hands, I can think, feel, and release at the same time. My work is very labor-intensive because of the craft techniques I use, and the time, energy and emotion invested in the creation process comes through in the work and back to those who encounter it.

This process is non-linear and relational. Ideas move back and forth between sketchbooks, doodles, writing, textiles, ceramics, sound and spatial arrangement. A creature may first appear as a small painting, then return as a ceramic object, and later evolve into a large-scale tapestry that you can sit or lean against. I’m interested in how motifs shift and change, like emotions. Nothing exists in isolation; Each action justifies and nourishes the others.

Craftsmanship is central to how I work. Techniques such as tufting, sewing and making ceramics by hand are slow, repetitive and physical, allowing space for reflection and bringing emotions to the surface. The labor itself is part of the meaning – sometimes the stitches become “angry”, sometimes the forms become soft and protective. Bright colors and playful aesthetics are deliberately used to gently explore deeper experiences, creating space for care, generosity and invitation rather than confrontation.

Ultimately, this process extends outward to the exhibition space. I think of establishments as hospitality environments: places that welcome visitors, encouraging comfort, conversation and togetherness. Audience participation is not an afterthought but an extension of the work’s ethics. My process feels complete when the work becomes a shared experience where it opens up space for connection, reflection, and mutual care.

‘Warrior Garments’ by Afra Isama | Photo Credit: Jules Lister

You have been vocal about sexual violence and trauma. Survival runs as an undercurrent through your work. You’re also creating space for the audience to process their own trauma. Does art provide a path to healing?

I don’t think art offers a path to healing, as if there is one clear path or solution. For me, art provides an outlet where healing can begin, stop, or simply linger. Working helps me process experiences that are too complex or painful to express in language yet. Through slow, labor-intensive craft and repetition, emotions are transferred through my body into the physical, and this is a form of healing in itself.

Sometimes healing begins with simply not being alone with the things you carry with you. I hope that my work can be a companion to those who have experienced sexual violence.

Surviving sexual violence can be very isolating, and that isolation can be dangerous. By explicitly addressing this experience and naming it as my work is created specifically for those who have gone through it, I hope to open up a space where people feel safe enough to identify, feel less alone, and normalize conversations around this topic.

Are the playful creatures in your work inspired by someone or something from your childhood?

They’re not directly inspired by specific characters or figures from my childhood, but they connect to my childlike way of imagining and engaging with the world. I wanted to create creatures that could provide the warmth of an embrace without being too human. Sometimes we want to be held or consoled, but human-to-human touch can feel complicated or overwhelming. By keeping these figures a little ethereal, they allow for a different kind of intimacy, where you’re completely in control of how much closeness or touch you want.

I am interested in the openness children often experience, their ability to invent companions, to move seamlessly between fantasy and reality, and to deal with heavy emotions through play. These creatures function somewhat like imaginary friends: They can hold difficult emotions without becoming overwhelming.

At the same time, they are largely shaped by my adult experiences. The playfulness is intentional because it creates an entry point that feels gentle and non-threatening. So while the figures may echo childhood imagery, they’re really about creating a shared, caring language in the present that creates space for vulnerability, safety, and connection.

From Kriti, ‘Warrior Apparel’ Photo Credit: Philipp Scholz Ritterman

What inspires you as a person and artist?

I am deeply influenced by literature and writers who imagine alternative ways of being and relating, such as Meenakshi Thirucode, Sara Ahmed, Ursula K. Le Guin and Audre Lorde. His thinking helps me understand emotions as political, collective, and transformative forces. I am also inspired by the artists around me such as: Carine Iturralde Nurnberg, Marnix Van Um, Afra Shafiq, and Buhlebezwe Siwani as well as those who came before, including Overtasi, Dorothy Iannone, Sister Gertrude Morgan, and Mrinalini Mukherjee.

What inspires me most is connection: between people, materials, emotions, and shared ways of imagining how we can hold each other and care for each other.

How would you describe your choice of content? How much of a role do materials play in your process?

Materials are at the center of my practice, they are not only containers for ideas, but also active elements of the work. I choose the bright colors of yarn, textiles, glazes for ceramics and other tactile materials for their materiality and responsiveness; Each material has its own weight, texture and rhythm. The softness of fabric allows intimacy and touch, ceramic maintains its shape while keeping a sense of fragility, and color becomes a way to direct emotions and attention.

What did you feel about the location of Kochi? Did space promote your work?

Kochi is a beautiful place, but it also holds an important history. The Dutch Warehouse, with its colonial past, reminded me how spaces are never neutral. They contain layers of power, displacement and memory. Soft, caring and playful forms permeate the site shaped by a history of control and extraction. Because the Dutch Warehouse is located in the heart of Fort Kochi, curator Arnika Ahaldaag and I felt it was important to create a space that encourages gathering, longer stays, and informal encounters. This aligns with how I want my institutions to function: as sites of care, reflection, and connection that tell about both personal and political histories.

What are your upcoming projects?

At the moment, I have started work for the Kinderbiennale (Children’s Biennale) at the Groninger Museum along with several other upcoming exhibitions. Part of the presentation at the Dutch warehouse will go to MAP in Bengaluru, which means I will be back in India in the spring.

Mild Tooth of Milk will be on display at the Dutch Warehouse in Fort Kochi till March 31.