Swadeshi nationalism, Bengali devotion and tobacco form an unlikely triad.

Yet I met all three of them on a cold Boston morning, over a poster that would almost certainly be considered anti-national by today’s hypersensitive standards.

Bengalis of the early 20th century certainly knew how to charm an audience.

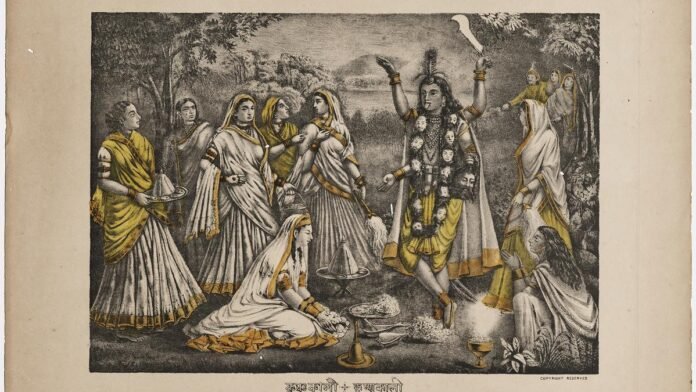

About Kali Calcutta Art Studio 1890-1900 Lithograph | Photo courtesy: Marshall H. Gould Fund; Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

At the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, this vivid poster of Kali is surrounded by carnage and delicately rendered text in blood red. On the sides, it praises the goddess as a protector, urging devotees to worship her image for courage. Below, is an advertisement for black cigarettes, proudly declared as ‘Pure Swadeshi’. (And, in typical misplaced optimism of that period, also “reliable, reliable and safe to smoke”.)

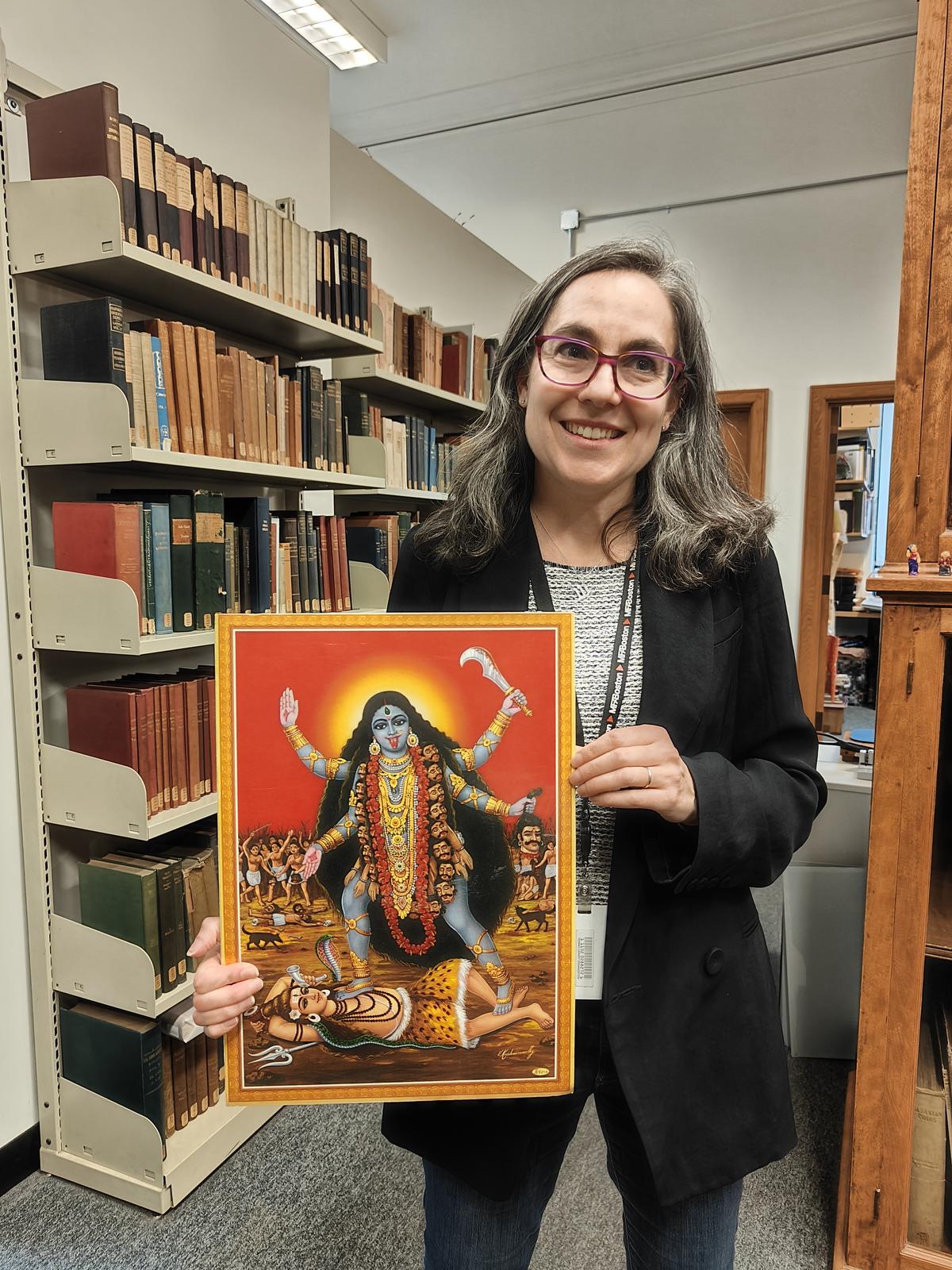

Laura Weinstein posing with a poster of Goddess Kali. Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

At the bottom, a printer’s note lists the maker: Calcutta Art Studio, 185 Bowbazar Street.

That’s where curator Laura Weinstein comes in. “We have put together people to think about where popular art from around the world comes from. And how it is connected to literature, street theater and local art forms,” she says, as she tells us about the bright historical prints that make up the museum’s latest exhibition, Divine Colours: Hindu Prints of Modern Bengal.

It brings together approximately 40 rare prints collected from around the world over approximately 15 years. Once ignored by serious art collectors, museums now value these prints. Despite being mass produced, they required considerable skill. Furthermore, rather than being passive art, they were created to be accessible, to be hung in homes, etc. Prayer Rooms are shaping history and people’s lives.

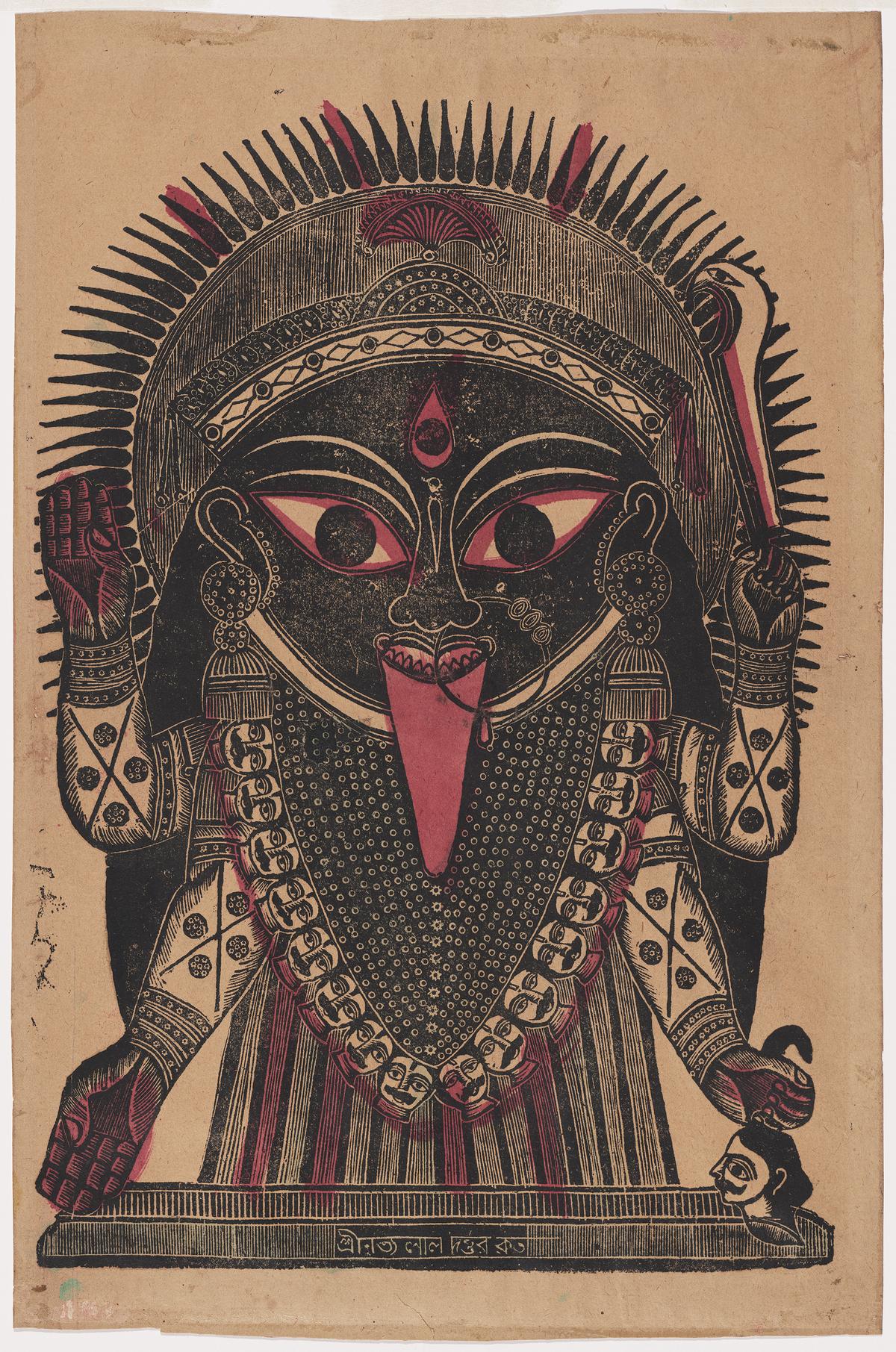

Kali Dance Lal Dutt (Indian) circa 1850-1880 Relief print, hand painted | Photo Credit: Private Collection, New York; Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Today, they are getting the museum display they deserve. And while the show is the first of its kind in the US, focusing on the work of Bengali artists from 19th-century Calcutta (now Kolkata), it is likely to spark interest in a whole new wave of collectors.

Divine Color includes paintings, sculpture and textiles as well as select loans from the museum’s South Asian collection, totaling approximately 100 objects.

“We are considered to have one of the best collections of Asian art in the world,” says Laura, who is the Anand Coomaraswamy Curator of South Asian and Islamic Art for the museum. The museum began collecting Indian art in 1917 thanks to Ananda Coomaraswamy, a Sri Lankan-British art historian. “He was in Sri Lanka in the early 1900s, where he collected bronzes. He came here with his collection and worked with the museum for the last three decades of his life,” says Laura.

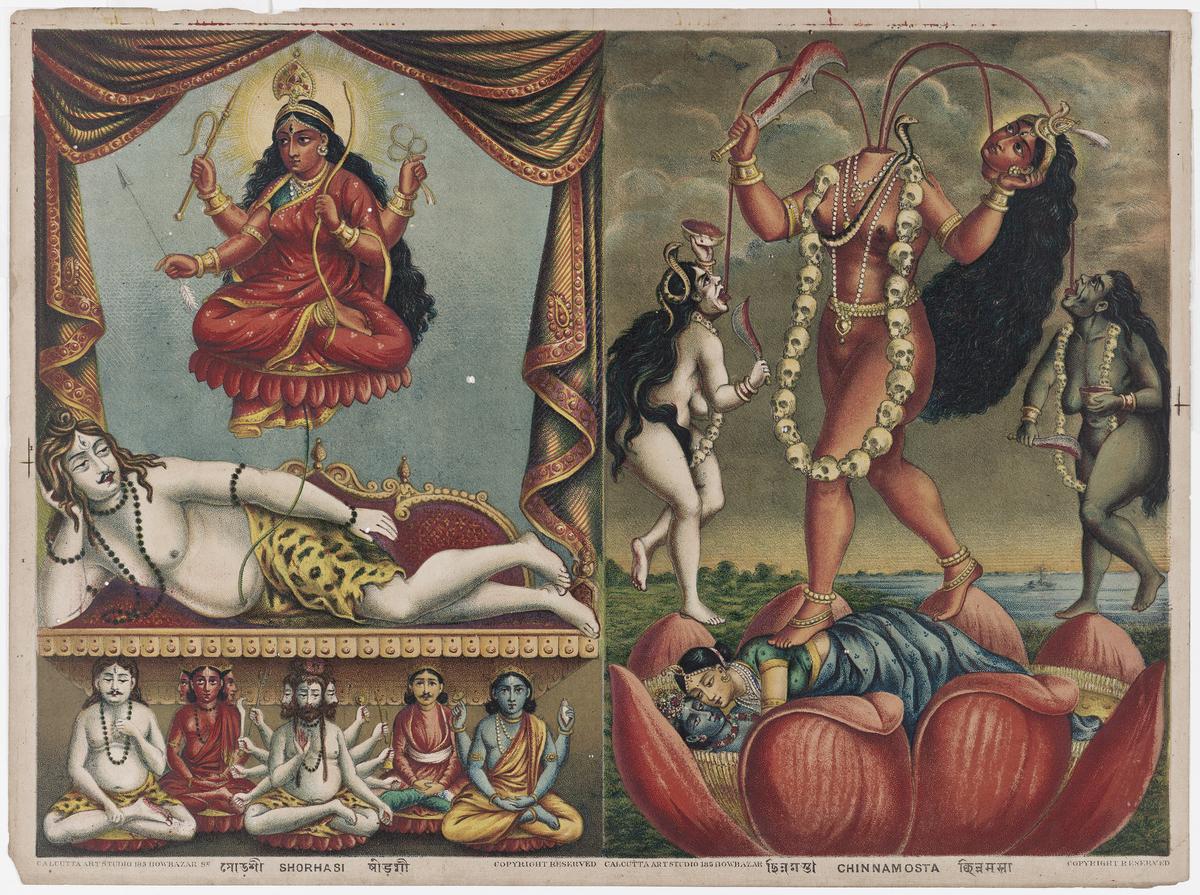

Kamala/Bhairavi Calcutta Art Studio 1885-95 About Lithograph | Photo courtesy: Marshall H. Gould Fund; Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

His interest in Indian art grew from growing up in New Jersey, “where the US has the largest Indian diaspora”. Inspired by his Indian classmates and friends, he spent a semester in Jaipur, then traveled to Varanasi.

explaining the importance of divine colorLaura gives us a class on lithography, which was invented in the late 18th century and arrived in India with Europeans, who used it for maps, lists, and census data. “By the 1850s, Bengali artists began using lithography presses to produce books for their own use. Then came portraits of political figures. When Kalighat artists learned the skill, they realized there was a large market for pictures of Hindu deities. It was a faster and cheaper process than painting. They began making pilgrimage souvenirs. It also became a way to convey political satire.”

Sri Sri Dashabhuja Calcutta Jubilee Art Studio, HP Bhoor (Indian) circa 1880-1885 Lithograph, hand painted in water color | Photo credit: John F. Frank B. Paramino, Boston sculptor, and in memory of the Edwin E. Jack Fund. Bemis Fund, Elizabeth M. and John F. Paramino Fund; Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Calcutta Art Studio, established in 1878, was the most famous of these Indian printing presses and produced iconic, mass-produced lithographs of Hindu deities. As she holds up a poster of Kali, Laura explains how her “Krishna Kali” prints were influenced by European realism. Now favorite objects of collectors, they were printed in ink, and then painted by hand.

Although they are becoming harder to find, Laura says, “A lot of these posters survive in Bangalore. There are a lot in Shekawati, Rajasthan, where they were used by Marwari families.” The museum’s collection began in 2011, acquired from art dealers and American yoga studios (which often bought them for display). She adds, “Today we have 75 prints, but over the last 15 years, Indian collectors have also grown interested in prints. So we probably won’t add any more.”

Shorhasi/Chinnamosta Calcutta Art Studio circa 1885-95 Lithograph | Photo courtesy: Gift of Mark Baron and Alice Boisante; Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Inspired by the Kali poster, I went online to look for Calcutta Art Studio and found that it still existed. Still on Bowbazar Road. Still printing. Still enjoying its past glory. Only now, it boasts “advice on packaging materials, offset machine spare parts and press layout” from its “brilliantly experienced team”.

It’s impressive – and completely in character – that the company is future-proofing itself in Kolkata. It’s fitting that, in Boston, its past is being preserved and celebrated with new audiences.

Divine Colors: Hindu Prints of Modern Bengal on view through May 31, 2026 Lois B. and Michael K. at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The turf can be seen in the gallery. Admission is included with general admission.

published – February 04, 2026 06:03 PM IST