Interviewing artists is like being given a puzzle and trying to figure out which piece, where, which part of the art was made. In the case of Sunil Gupta, the internationally renowned photographer makes it easy for us. For nearly five decades, he has removed his work from his life, and the membrane between the outside and the inside has grown thin.

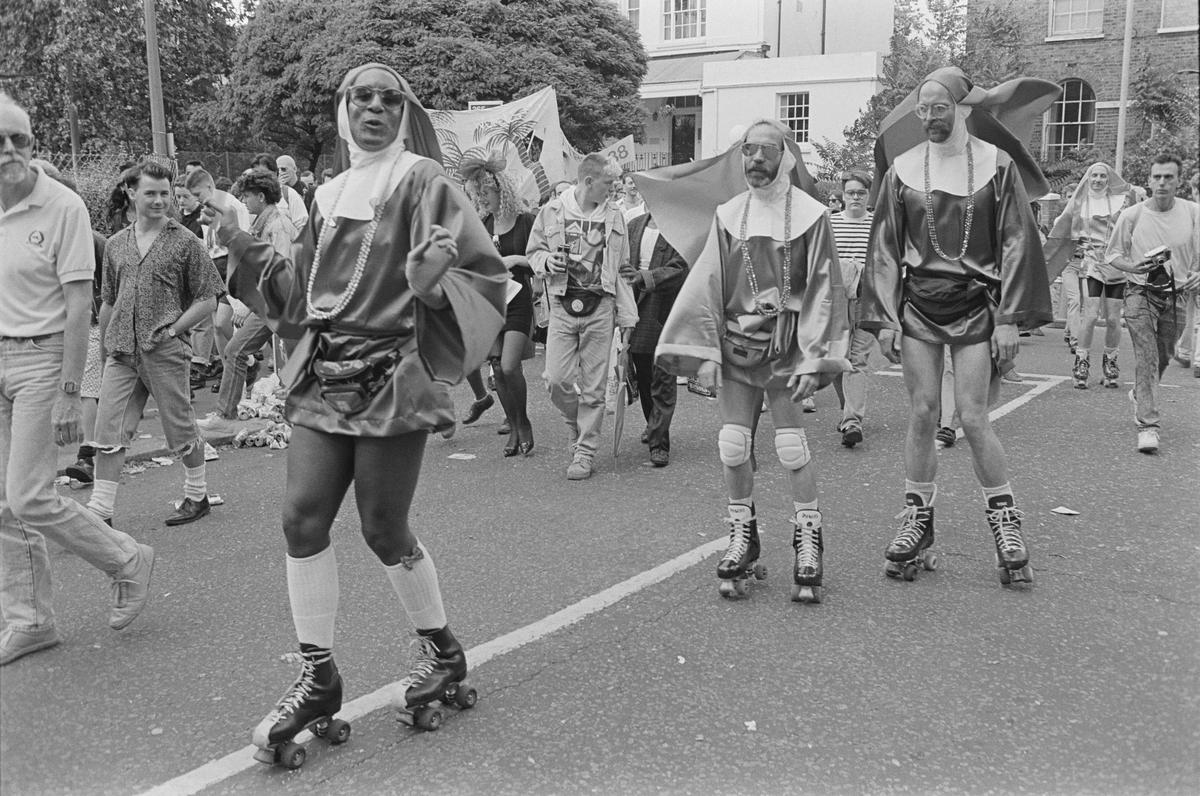

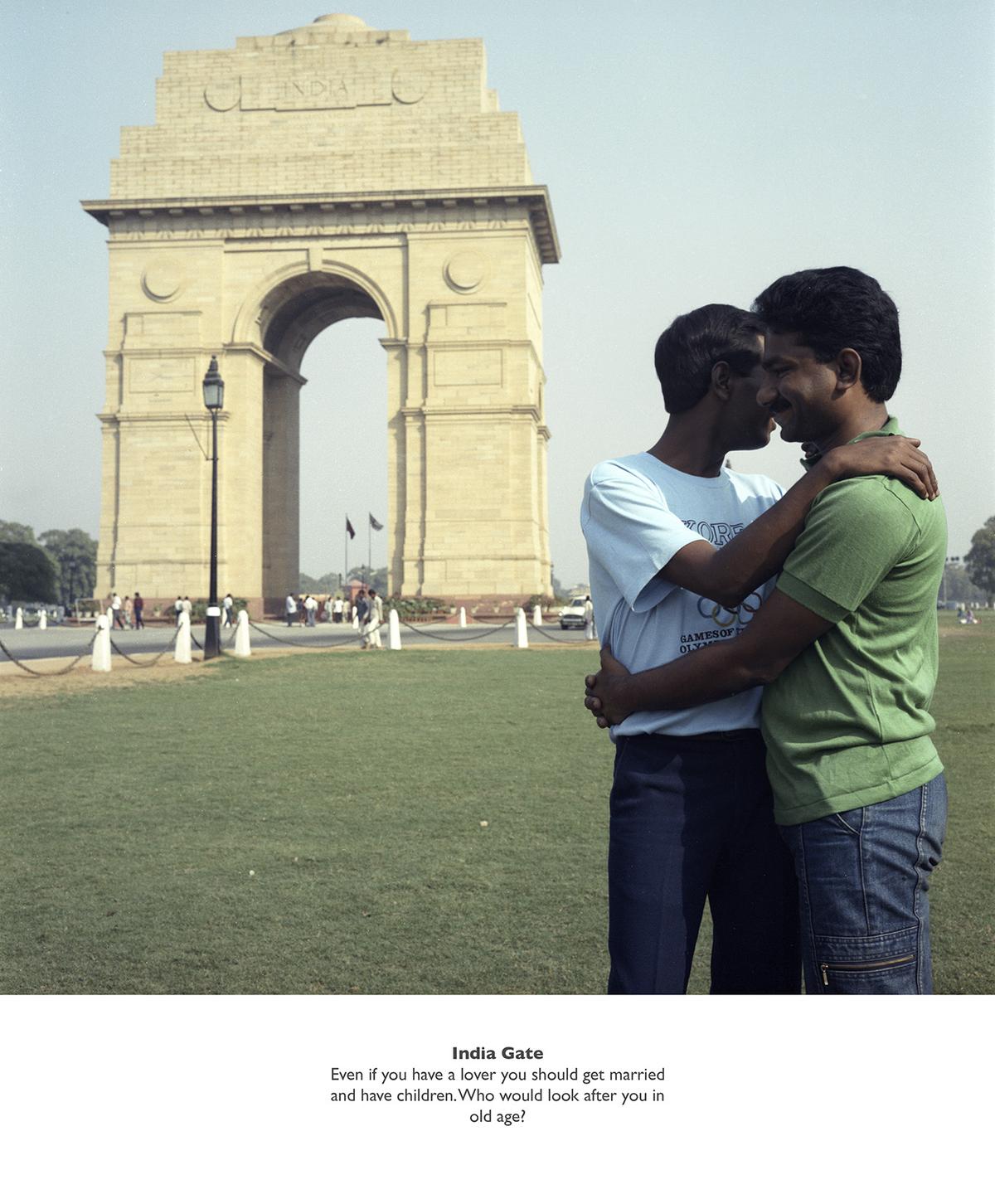

Born in New Delhi in 1953, Sunil’s family moved to Montreal in 1969 when he was 15. After coming to Canada, as he embraced his gay identity, he became part of the gay liberation movement, and expanded his view of family (Friends and Lovers: Coming Out in Montreal in the 1970s); His move to New York in 1976, following his boyfriend, and seeing gay men coming out, feeling proud, and walking (Christopher StreetUntil his move to London and subsequent break-up where he used the camera to investigate relationships, making portraits of gay couples (Lover: Ten Years LaterHe made a record of visiting India in the 80’s and seeing them married and living a secret life (brothers), and was diagnosed as HIV positive in the mid-90s and again came to terms with his body and love (love, didn’t knowSunil has taken the feminist slogan of personal is political to heart.

Photographer Sunil Gupta

As soon as I come on video call with her and Charan Singh or husbandYes Since he is lovingly labeled on Instagram – he is also an artist, and the curator of this first Indian retrospective at the Chennai Photo Biennale – I feel a sense of kinship about Sunil. It is an artificial construct that is a combination of living in Delhi around the same time (2005-2015), Sunil’s name coming up frequently at work during my time as a journalist, and a sense of joy put together. And the victory that followed the original repeal of Article 377 in 2009, which included many of my friends, like Sunil, and was probably on the way. brothers It has permeated our collective consciousness.

‘Indians did not exist’

Of course, I have never met him, nor do we live in Delhi anymore. Sunil and Singh have been living in London since 2012, and I am in Hyderabad and we are talking about how Sunil’s work will be shown in Chennai, at the Egmore Museum, one of the city’s central monuments.

Topic Love and Light: A Place of Infinite PossibilitiesIt presents five decades of the gay rights movement and the gay community at large in Canada, Britain and India, says Varun Gupta, director of the Chennai Photo Biennale. But Singh’s curation is also a love letter of sorts. “I think this show has combined the personal, the private, the public, all together.”

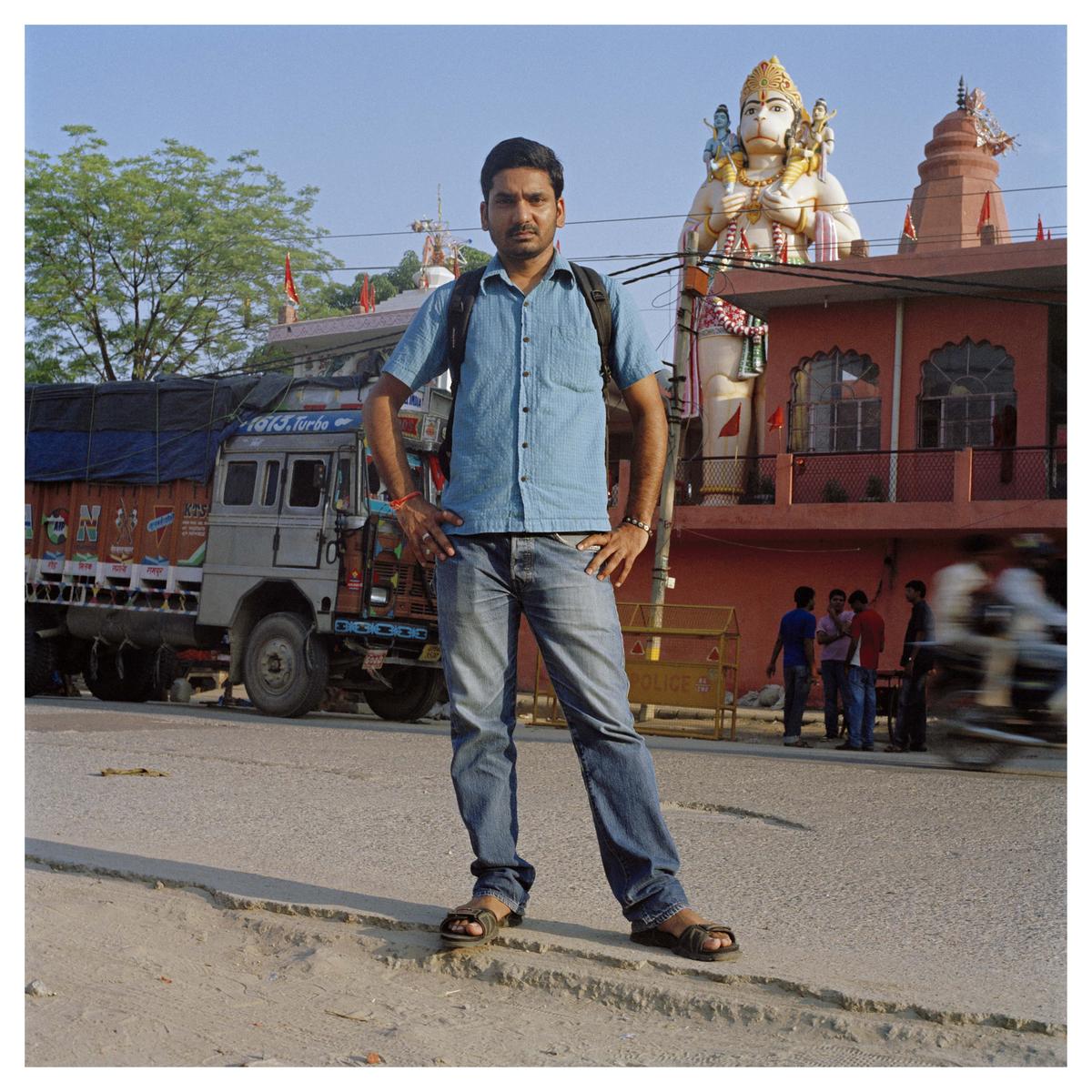

Sunil and Singh met in 2009 when Sunil was in India. Singh was working with people suffering from HIV/AIDS. He says that he was surprised that Sunil took pictures of his friends and then put them on the wall and called it art. “I think it was also a reaction to his previous photography. People did not take him seriously, but now they can see his steadfastness in his approach and devotion towards that one issue – which is to bring [Indian] “Lesbian images in artwork, in discourse, in dialogue, and in museums.”

Sunil has spent his career trying to ensure the representation of first gay men in art history and then gay men of Indian origin in the field. He talks about how this was partly driven by the feeling that as an Indian male, he did not feel like his body was particularly desirable because there were no pictures of Indian male bodies. Western porn was all white or black men with the occasional Chinese included. “But Indians? No, I never saw them. “It seems as if they don’t exist.”

In the 80s, artists like Robert Mapplethorpe were leading public discussions on what it meant to be a gay photographer with images of the body and gender. “And I used to tell people, honestly, that part of my biology is not a problem. The problem is with everything else, how our relationships are, how we can’t have them, how we aren’t allowed to have them. It was all these other social things that were the problem,” says Sunil.

Deported India Gate Photo Courtesy: Sunil Gupta

Ensuring spotlight on AIDS

Recently, Sunil’s work has fueled the movement towards HIV/AIDS awareness. Although it may seem as if we are living in a post-HIV world, this is hardly the case. “Culturally, there’s a revival happening here,” he says. “There has been a strong cultural force, starting in the 2000s in New York, saying that, hello, AIDS is still here.”

Even though governments are cutting funding for awareness programs, the revival of the 80s as a decade in popular culture is ensuring a spotlight on AIDS, one of the defining characteristics of the decade. Sunil’s show and book, Bliss AntibodiesNow the investigation is being done again since 1990. “Young people want to know more about it. It’s still a current issue,” he says.

Sunil has long used his personality to attract people to queer art, artists, and gay community issues. Roshni Vadehra, director of Sunil’s long-standing gallery, Vadehra Art Gallery in India, remembers meeting the photographer early in his career in 2008, when Sunil co-curated an exhibition for him. Click! Contemporary photography in India“During that project, I became familiar with his practice and found it to be a unique and important voice in contemporary art, noting that it drew attention to issues that had not been addressed and to social and political forms. Full attention was given to them. Even though there was no active market for his work at the time, or for photography in general, there was tremendous engagement and this brought a wide variety of audiences to the gallery as Sunil became a popular figure within the art world and the gay community at large. Was a person. ” Perhaps we’ll see more of this in an upcoming Indian retrospective.

Chennai Photo Biennale is organized in association with The Hindu.

The author is a photographer and writer.

published – January 17, 2025 12:11 pm IST