The history of photography in India goes hand in hand with the development of the modern science of anthropology. In the mid-19th century, colonial officials, army surgeons, missionaries and government photographers took heavy cameras and delicate glass plates to cities, battlefields and mountain passes in an effort to ‘objectively’ document the country’s people for administration and governance.

But fairness is questionable. Working in makeshift camps and studio tents, he photographed men, women and children as “types”: Brahmins and Bhils, traders and soldiers, frontier tribes and court artists. Under ambitious projects like people of indiaResulting in an eight-volume series (published between 1868 and 1875) compiled by John Forbes Watson and John William Kay, entire communities were turned into catalog entries, their portraits paired with captions that evaluated character, behavior, and social value. (These volumes were produced after the Rebellion of 1857, when the British felt the need to “know” India.) Marketed as neutral and objective, the camera became one of the most powerful bureaucratic tools of colonialism.

people of india cover Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

“The photographs in themselves do not suggest that they were made with a colonial vision,” says historian Sudeshna Guha, who delved into the DAG’s archives to organize a comprehensive exhibition of colonial-era photographs, titled Typecasting: Photographing the People of India 1855-1920. “The typology was created not only by the British, but also through information from the natives [what they shared about their caste, creed, occupation and trade]. Many photographs do not have a background; Therefore they appear to be alienated from the cultural plane. That typology is a creation – ours – it’s what I want visitors to get.

Manure Drier, Bombay; Attributed to Edward Torrance. Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

‘Making a type invisible’

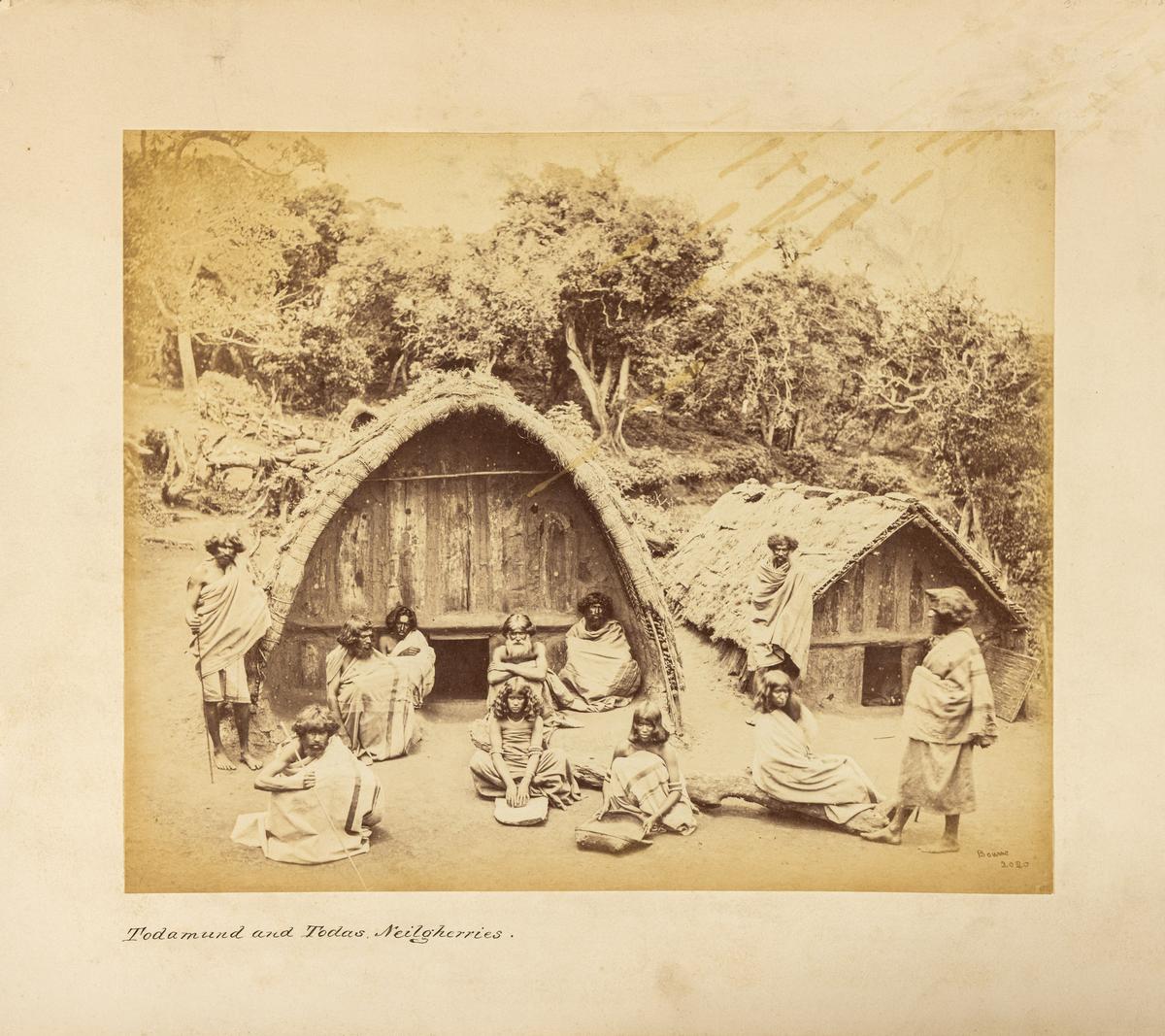

Running parallel to the India Art Fair, typecasting It brings together approximately 200 rare photographs and photographic objects, including albumen and gelatin silver prints, cabinet cards and postcards, spanning an extraordinary geographical and community range. The images span across tribes, ‘races’ and trades, such as the Lepchas and Bhutias of the northeast, the Afridis of the Khyber Pass in the northwest, and the Todas in the Nilgiris in the south, as well as wealthy Parsi and Gujarati families, dancing girls, porters, barbers and snake charmers.

A. Todamund (Eucalyptus); By Samuel Bourne | Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

At the center of the exhibition is a rare selection of folios people of indiaIncluding the work of some of the best amateur photographers of the 19th century, including Benjamin Simpson, James Waterhouse and John Burke, and the lesser-known commercial studio Shepherd and Robertson. “The idea is to show the power and potential of a photograph to question typology,” says Guha. She points to paintings painted by Simpson of people of the Lepcha Bhutia tribe in 1861–62. It was intended to be an authentic representation of the community, but was photographed in Darjeeling, not Sikkim or Tibet.

A group of young ghosts, attributed to Fred Ehrle. Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

an obscure record

In an accompanying publication, which includes essays by Professor Ranu Roychowdhury (Ahmedabad University), Suryanandini Narayan (Jawaharlal Nehru University) and independent researcher Omar Khan, Guha articulates the ways in which all photographs taken at that time may have been composed, or “staged”, as a result of the constraints of time. In the 19th century, photography was a physically demanding and technically delicate process.

Many early photographers worked with the wet collodion method, which required glass plates to be coated, exposed, and developed while wet, so they were forced to carry portable darkrooms, chemicals, water, and light-proof tents wherever they went. Heat and moisture routinely destabilized chemical reactions, destroyed negative elements, and caused emulsions to peel or crack. Long exposures meant that subjects had to remain completely still, creating the harsh, haggard look that became typical of ethnographic images.

Untitled (Portrait of a Native Woman); By Hurrichund Chintaman, Bombay | Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

“The complaint among the British was always that you ask the original subject to stand still, but as soon as you’re going to click that picture, he does something to go out of focus,” says Guha, “Samuel Bourne complained about the fact that dark faces become so dark next to the sun, especially if the subject is also wearing white clothes.” turban“

Cookie. Robber tribes. Cachar (Assam); By Benjamin Simpson | Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

Plates broke during transit, daylight diminished rapidly and monsoon conditions damaged equipment. Despite these obvious shortcomings, the finished photographs were presented as accurate scientific records, hiding the messy realities of climate, reclamation, and human interactions that shaped every image. “The camera captures whatever is put in front of it and doesn’t discriminate,” she adds. “So, in a way, photographs become a kind of invisible.”

Guha’s hope is that, more than a century after the last of these images were taken, visitors will be able to train their critical eye on these images, and consider not only what they ‘depict’, but also the ambiguities they reveal. He also includes photographs by 19th-century Indian photographer Daroga Abbas Ali, which capture the vibrant world of Lucknow’s dancers and royal artists, capturing a cultural scene that colonial photography often ignores.

Brahmin girls; By William Johnson | Photo Credit: Courtesy DAG

It is also worth noting that, despite the problematic colonial history from which they emerge, each photograph in the exhibition is fascinating to look at, and could potentially open up new areas of historical inquiry. Guha concluded, “More than anything, I hope some bright young sparks will think about this and realize that there is a lot more research to be done on this period.”

Typecasting can be seen at Bikaner House, New Delhi till 15th February.

Freelance writer and playwright based in Mumbai.

published – February 06, 2026 11:20 am IST