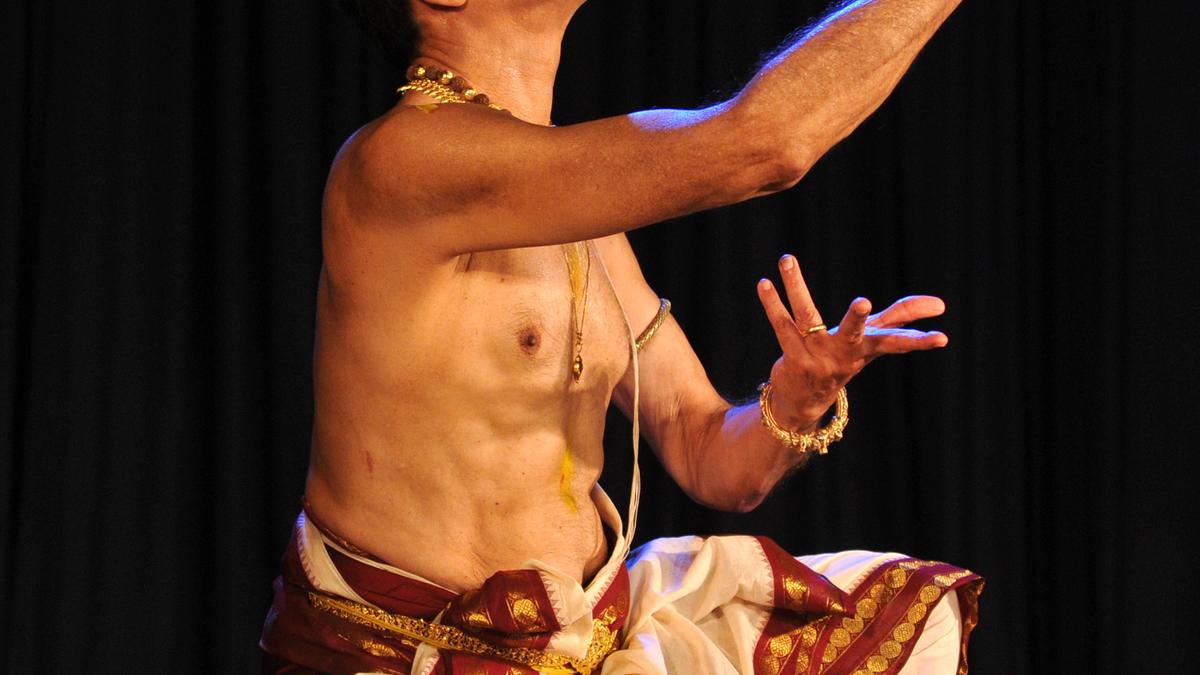

C.V. Chandrasekhar during a presentation at the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in Mylapore, Chennai. | Photo credit: Jothi Ramalingam B

One has to climb a flight of stairs to reach the Faculty of Performing Arts of Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. The brick façade and the distinctive wooden architecture seem to hold within themselves a piece of the country’s rich cultural past.

It was a warm morning in June 1987, and C.V. Chandrasekhar (fondly called C.V.C.), the Head of the Department, was in his office. He sat upright in his chair, clearly explaining to those of us who had come to take the entrance exam what the tough course involved. Seeing our nervous expressions, he consoled us the very next moment, saying that it was not bad to be afraid of challenges, but that it should not come in the way of pursuing one’s passion. Behind the disciplinary cover was a committed teacher who was ready to help us embrace both the rigours and the excitement of the journey.

The campus resounded with the sound of dancing feet and instruments as the CVC stood up and walked into the large prayer and practice room. As soon as he entered, there was silence and the students quickly arranged themselves in straight rows. The girls were dressed in Bharatanatyam training attire, hair neatly tied in a bun or plait, a bindi on the forehead and matching bangles and earrings. The boys, who were fewer in number, wore white cotton dhotis and short kurtas. Under the sharp gaze of their guru, they began praying. Their eloquent hands made different gestures and bodies assumed different postures. For the CVC, training was not confined to mastering the technique, it also extended to immaculate looks and the right attitude.

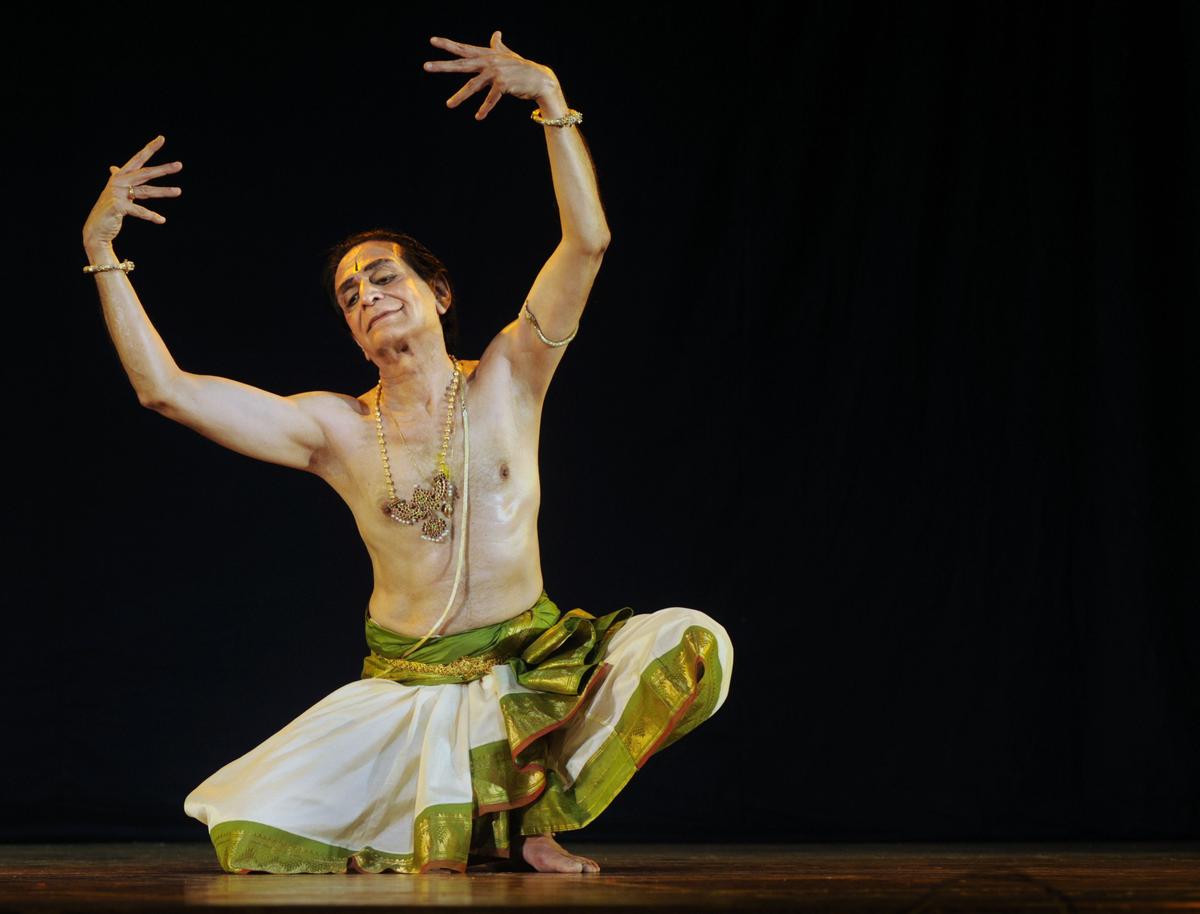

C.V. Chandrasekhar performing at the Narada Gana Sabha in Chennai on December 16, 2009. | Photo credit: Ravindran R.

After the prayers were over, the students of the first and second year of the undergraduate course went to their respective classes while the senior students stayed back to perform the padam taught by C.V.C. Thatukazai (used for nattuvangam), he indicated his displeasure or satisfaction through his eyes and facial expressions. The students watched in amazement as he paused to talk about the need to internalise rhythm, words and emotions.

As a guru and artist, CVC’s personality remained the same. Humble and forthright are the personalities that come to mind when you meet him. His belief in his art was so strong and deep that he did not compromise or favour in any way. With a perfectly aligned body, his movements were a blend of intense physicality and intellectual sensitivity. His expressive face brought alive the lyrics of the compositions he danced to.

C.V. Chandrasekhar during a lecture demonstration at The Music Academy in Chennai on January 05, 2008. | Photo Credit: Ganesan V.

After a teaching stint in Baroda, CVC moved to Chennai, where he trained under unique gurus at Kalakshetra. It was here that his guru, Rukmini Devi, opened his eyes to the possibilities of the world of dance and beyond.

CVC grappled with the changes that were taking place in the art form at the time, but his approach to dance remained reverential. And this approach often disappointed him as he felt the emphasis on contemporaneity left no room for soul.

Though gradually he came to terms with the idea of performing for a new-age audience, for him dance was not a performance, it was an intimate exercise, a sharing of emotions.

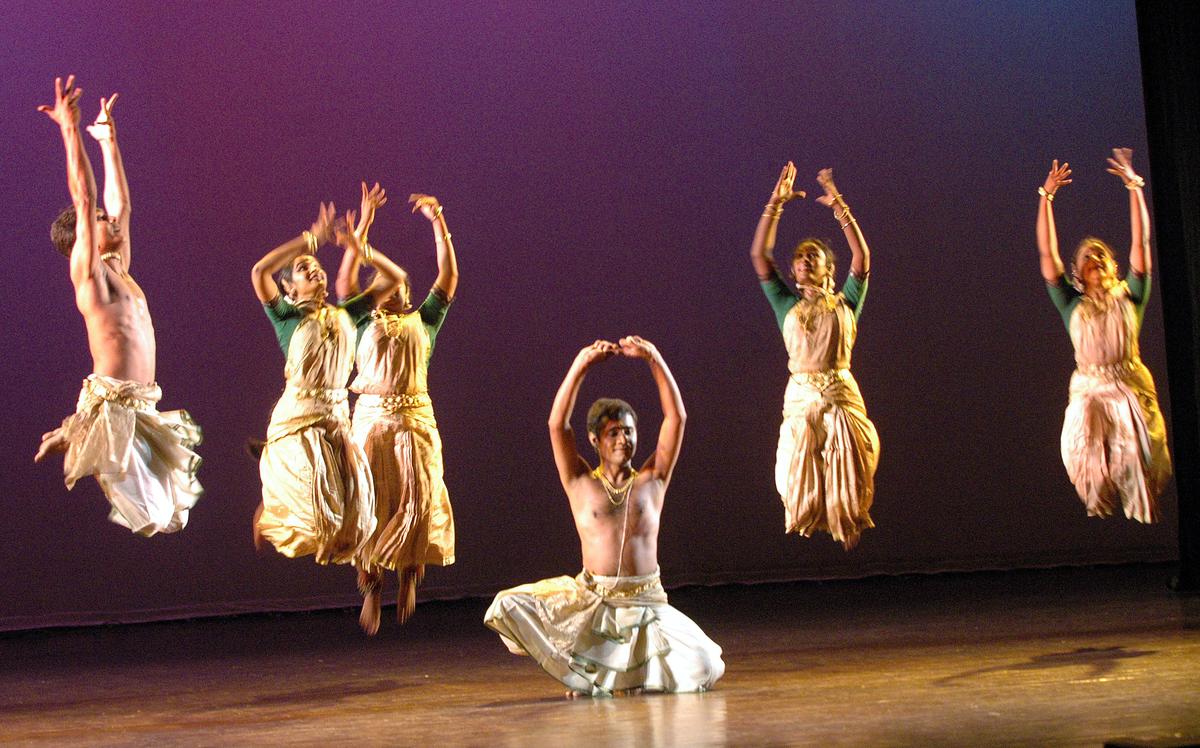

C.V. Chandrasekhar’s students performing for the Parampara Mahotsav at the Kamani Auditorium in New Delhi on September 24, 2005. | Photo courtesy: Sandeep Saxena

Once when I met him after an experimental performance, he was a little taken aback by this artist’s quirky approach to the form. He always reiterated that dance should not be seen in isolation. Innovation should happen naturally. The most important aspect of his creative work was the close relationship between movement and music. Apart from being an influential artist and choreographer, CVC also sang and composed music. His works expressed the potential and power of dance as an expression of the human spirit – they were the result of his long, arduous journey of learning and discovery and his struggle to find acceptance as a male Bharatanatyam dancer. Yet he created a niche for himself at his own pace and on his own terms.