Some pop-culture artifacts have cross-cultural resonance Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama,

The epic has long served as the country’s guiding star, endlessly adapting to the shifting tides of its storytellers. But for Millennials and Gen Is in a different location. dip-doo Mystery, Shaktiman Episodes and other figments of childhood nostalgia.

The Indo-Japanese anime collaboration that first graced Indian screens in the early 1990s has seared itself into the collective consciousness partly for just how beautiful it looks and partly for the sheer audacity of its creation. . It has since braved storms of misunderstanding, political controversy, and technological advancements to arrive in dazzling 4K glory on Indian screens three decades later. For a story that explores cosmic battles and moral dilemmas, the film’s journey at the Indian box office is no less epic.

You have to rewind to the film’s inception to understand this. The legend of Prince Rama Still commands Shraddha. In the early 1980s, Japanese filmmaker Yugo Sako stumbled upon the Ramayana while working on a documentary about archaeological digs in Uttar Pradesh Ramayana remains.

Enchanted by the breathtaking depth of the story, Saeko read ten versions of the Ramayana in Japanese, convinced that only animation could do justice to its divine, mythological scale. Live-action, he argued, could never capture the essence of the titular God without the limitations of mere mortal actors.

It’s a strange, almost poetic irony that Bibi Lal’s legacy connects so deeply. The legend of Prince Rama. Lal’s archaeological work at Ramayana sites fascinated Sacco and planted the seeds for his animated adaptation. But it was also Lal’s later controversial claims about the discovery of the pillar bases beneath the Babri Masjid that would stoke the fire of the Ayodhya dispute that culminated in the destruction of the mosque in 1992. himself a polarizing figure in history as the chronicler of the Ramayana’s mythological past and its very real, modern turmoil. The fact is that Sacco’s animated vision of the Ramayana must share its origins with the political tensions that uneasily simmered in Ayodhya lingers. It feels like a depressing commentary on how mythology can be achieved simultaneously as art and weapon.

But in India, Sacco’s ambitions were unsurprisingly still met with skepticism.

The Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) opposed the idea of a “foreigner” adopting the epic, mistaking its intentions as pious. The Indian government, mindful of political sensitivities during the height of the Ayodhya dispute, refused to cooperate on the project.

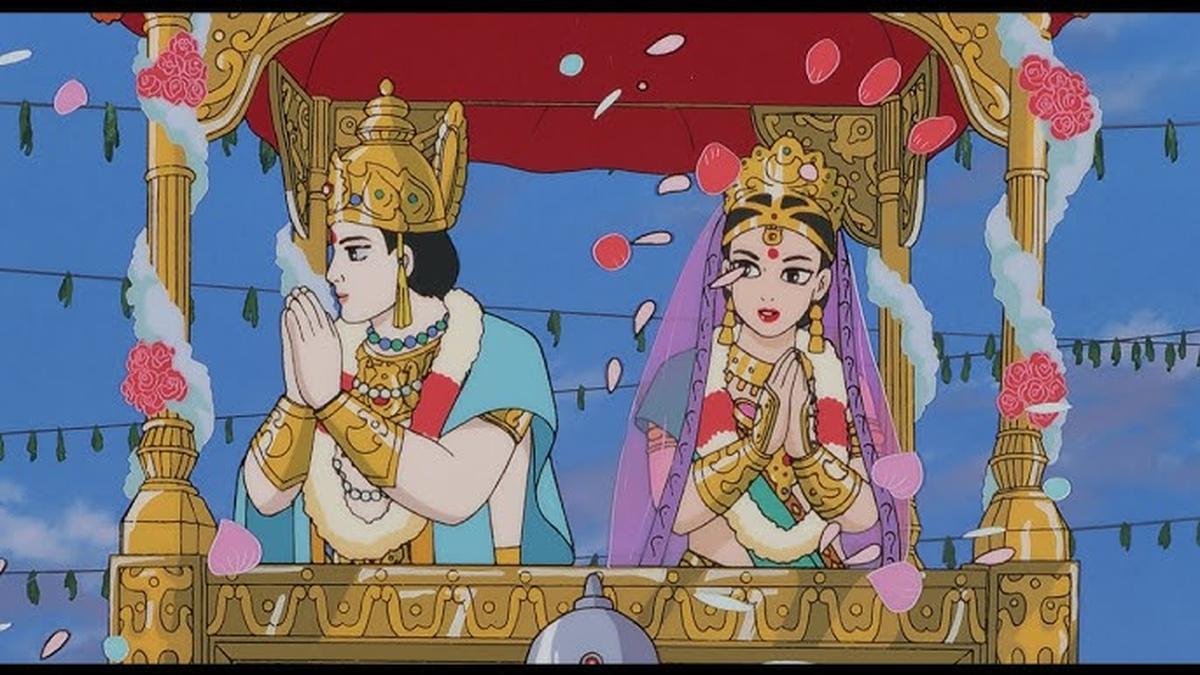

A still from ‘Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama’

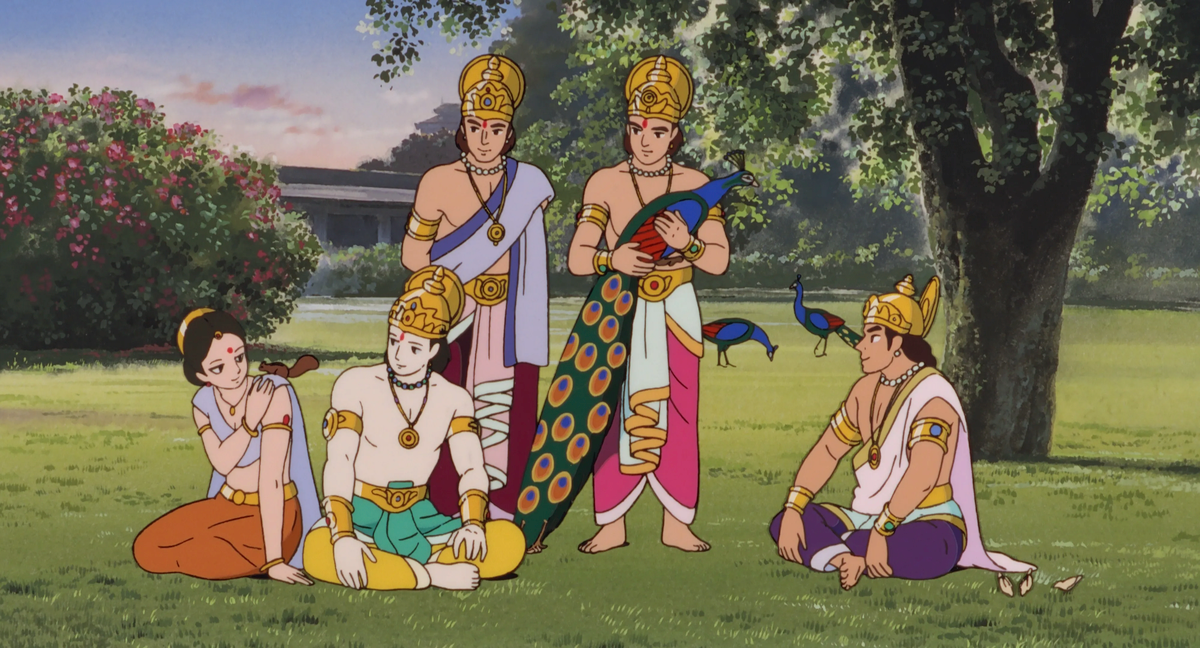

Undeterred, Sako took the project to Japan, where he secured funding and formed a unique production partnership. Indian animators such as Ram Mohan worked with Japanese studios, bridging the two different storytelling traditions. Cultural accuracy was paramount – Indian animators taught their Japanese counterparts the finer points of draping dhotis and performing namaskar.

By 1993, the film premiered at the International Film Festival of India and later at festivals in Vancouver and Tokyo to critical acclaim. Nevertheless, its dramatic possibilities were affected by the political sensitivities of the time. Its limited distribution meant that for most Indian audiences, the film existed primarily as a fleeting memory from TV reruns on Cartoon Network or worn-out DVD copies. It then languished in relative obscurity, surfacing sporadically on television and YouTube.

This is part of what makes temporary travel The legend of Prince Rama So compelling. The animation itself is stunning, even by today’s standards. Meticulously hand-crafted frames imbue the story with a timeless quality, far removed from the clunky CGI abominations of recent reinterpretations like the 2010 Ramayana: The Epic or 2023 Adipursh. Every scene seems to be crafted with a love for art, be it the quiet moments of Rama and Lakshman’s exile or the grandeur of the battle in Lanka.

But the true triumph of the film, beyond its Ghibli-esque charm, has always been in its ability to distill the essence of the Ramayana without diluting its spiritual gravity for a more informed modern audience. The characters may appear a little pale (which is a stylistic concession to Japanese anime norms), but the depth of its characters is unmistakable. Sacco’s approach also bombs for subtlety and balances the moral dilemmas and divine destiny of its storied mythology, which is what makes it so human.

A still from ‘Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama’

4K re-release Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama offers a chance to see this animated gem as it was meant to be seen – crisp, vibrant, and heart-wrenching in the original Hindi dub. Yes, the dub that boasted Bollywood icons like Shatrughan Sinha and Amrishi Puri has vanished into the ether, a casualty of time and, perhaps, cultural amnesia. For those coming to theatres, whether to relive a long-ago childhood or to indoctrinate their offspring in the gospel of Rama, Ugo Sako’s adaptation shows the indelible impact of anime on an Indian audience that once Is accessible and thought-provoking.

As India and Japan celebrate 70 years of diplomatic relations in 2022, the long-delayed return of this cult classic to the big screen feels like at least a formal nod to that partnership. Still, after mysteriously missing its slated release last September, the timing of its reappearance may raise some eyebrows, given its alignment with the first anniversary of the construction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya this month. Happened.

Still, the anime is a cool corrective to the recent misfires of the overwatch spectrum and attempts to remix Ramayan for TikTok sensibilities. The legend of Prince Rama What a respectful adaptation looks like. It neither provokes nor does it pedantize; It simply tells the story with honesty and grace, albeit with a convenient slight to the history of noise that has surrounded it.

published – January 25, 2025 03:22 PM IST