Looking at a friendship that has lasted for nearly four decades is no easy task, but art critic, cultural theorist and poet Ranjit Hoskote has managed to do so with his characteristic finesse. Breaking and Branching Out: Six Essays on Giva PatelPublished by Seagull Books, the book is a celebration of Hoskote’s long and deep association with the artistic works of Patel, who was a painter, sculptor, translator, poet, teacher, playwright and a practising physician. Patel died last November at the age of 83. Hoskote shared some fond memories. Edited excerpts:

When Nissim Ezekiel introduced you to Geev Patel, what was your first impression of him?

I was in my late teens when I first met Gieve, Nissim introduced me to him at his famous PEN All-India Centre office on the ground floor of Theosophy Hall in Mumbai, which has long been a venue for happy meetings, lively gatherings and intense conversations. I had read some of Gieve’s poetry at that time, and he was already a name that came to mind for me. Like many of us, I had read his poem ‘On Killing a Tree’ at school, and immediately found him affable. He was a warm personality, affable, charming. We connected.

Gieß said to you when you were in your mid-20s: “To write really meaningful poetry, you have to go very deep, to where things are broken.” How has that advice helped you?

I must confess that at the time Geev gave me this advice, I found myself rebelling against it. It was a time when I was stepping outside myself to engage with bigger things, causes and urgencies. I was taking on big themes – myth, epic, history – and developing a kind of baroque poetry. As I stabilized – and, possibly, grew up – big things and big themes began to find resonance and inner reality in smaller, more intimate, everyday contexts. At this stage, and as life and time began to impart their tragic wisdom, Geev’s advice assumed vital importance and resonance for me. I believe – at least, I hope and trust – that my poetry has benefited greatly from his advice.

‘Embrace’ (2016) by Give Patel

How did Geev’s encounter with the work of J. Krishnamurti and his time spent at the Mirtola Ashram in the foothills of the Himalayas influence the way he viewed things, people and life?

Accepting the reality of spiritual experience was part of Geev’s gradual process, during which he came to see clearly the limitations of skepticism, which prized rationality above all other ways of approaching the world. Through his encounters with devotion and spiritualism, Geev began to find ways of being in the world that allowed him to combine skepticism with wonder, restraint with joy in the beauty of the present moment, and to think about belonging within a larger context of interconnections between sentient beings and the universe.

Geev translated the Gujarati poet Akho. You translated Lal Ded. What overlapping themes did you find in the poems of these mystics?

Despite belonging to different places, periods and spiritual affiliations, both Lal Ded and Akho were impatient with organised religion, which pretended to be exclusive piety. They sought to free the soul from ritualistic concepts of religious life. They expanded the range of emotional expression available to the explorer.

Gieve’s painting ‘Off Lamington Road’ is on the cover of your book. What does it represent to you?

Gieves off Lamington Road It reflects that memorable combination of everyday life and fantasy that gave his paintings a distinctive quality. On one level, it is meant, quite literally, to depict the view from Gieve’s clinic, which was located on Lamington Road, around the corner from Mumbai Central Station. But look closely, and mystical elements reveal themselves: in the upper right-hand corner of this large work is a giant parrot hanging upside down, above a group of revelers dancing and drumming in the street.

In the distance, a riderless horse appears from behind a wall – we take a moment to understand that perhaps a carriage is following, but in itself, the horse appears to us as an omen, an omen. Everywhere, the currents and eddies of human life carry us along or bring us to a standstill – and when we are immersed in this memory of a busy street in the middle of Mumbai, we recognise that this painting is in fact a visionary tribute to the Sienese painters whose work Giovanni loved so much – for example, to the vastly populated civic panoramas of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s multi-part fresco programme, Allegory of good and bad government.

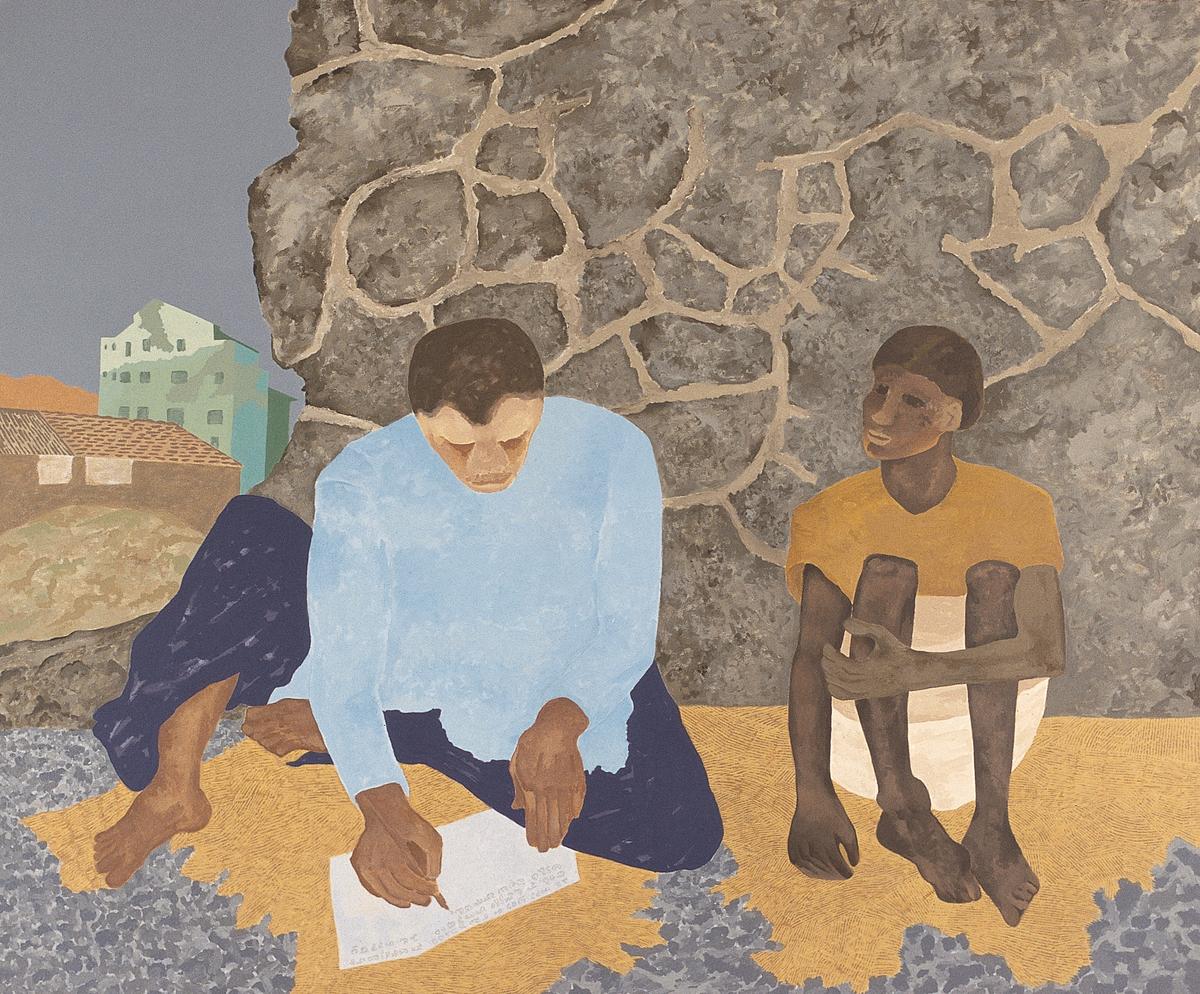

The Letter Home (2002) by Geev Patel

You have acted in plays written by Givey and directed by his wife Antoinette. Their daughter Avan has directed plays you have written. How did this friendship extend to other members of the family?

Both Nancy’s [cultural theorist and curator Nancy Adajania, who is married to Hoskote] Geev and I were very close and were quickly adopted by the family. We collaborated in different ways with Geev, Tony and Avan at cultural events; we all attended parallel cinema film screenings in the late 1980s and ’90s, and participated together in both the visual arts and the literary arts for decades.

In addition, Gieve and Nancy had their own relationship, independent of mine, based on their strong connections to the specific life-world of the rural Parsis of Gujarat. This gave them both a very strong awareness – from a position of privilege but with a keen awareness of the need for reform – of the problems faced by the rural underclass, particularly those belonging to the tribal communities, as helpers, or workers, or cultivators.

In Geev’s case, this led to compelling works such as his play, Mr. BehramWhere one of its main characters is a Warli boy adopted by a Parsi lawyer, and the image of Eklavya, the tribal prince brutally tortured by his Brahmin teacher, features in his later paintings. With Nancy, it has sustained a lifelong commitment to artists of rural, tribal or otherwise subaltern heritage – to placing them at the leading edge of contemporary cultural expression.

The interviewees live in Mumbai and write on books, art, gender, film, education and peace initiatives.