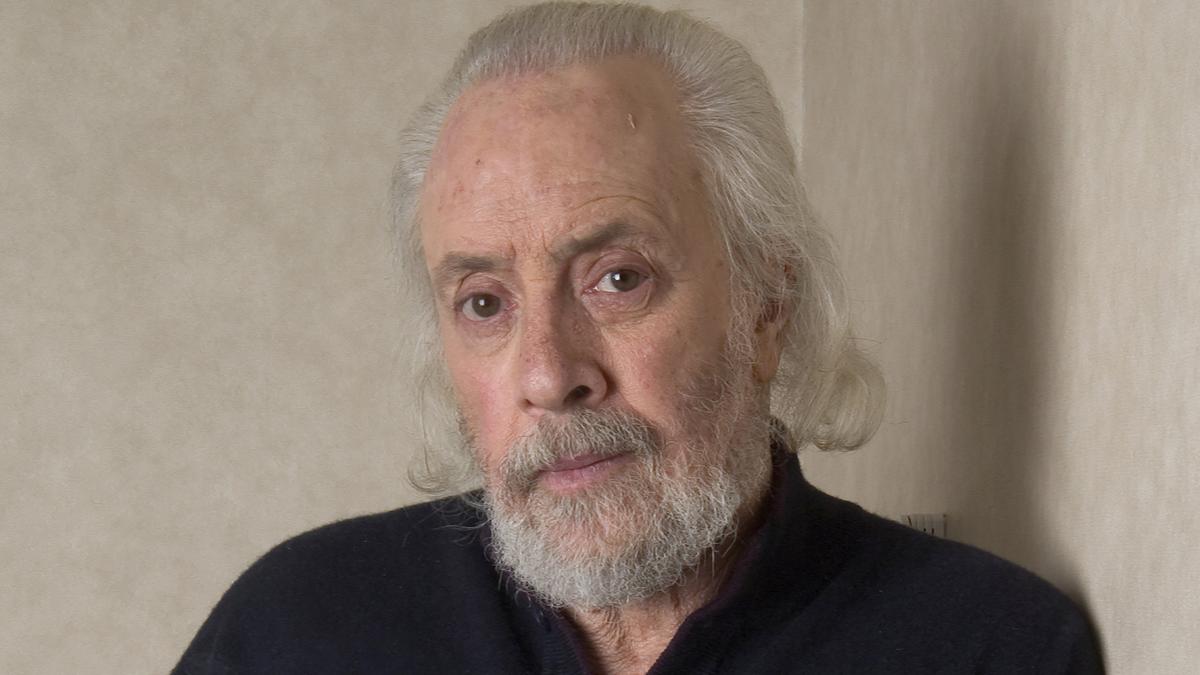

Robert Towne, the Oscar-winning screenwriter of “Shampoo,” “The Last Detail” and other acclaimed films whose work on “Chinatown” became a model for art and helped define the edgy charm of his native Los Angeles, has died. He was 89.

Towne died Monday at his home in Los Angeles surrounded by family, publicist Carrie McClure said. She declined to comment on any cause of death.

In an industry that gave rise to sad jokes about the status of the writer, Towne at one time acquired a reputation equal to that of the actors and directors with whom he worked. Through his friendship with two of the biggest stars of the 1960s and ’70s, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson, he wrote or co-wrote some of the signature films of an era when artists had an unusual degree of creative control. The rare “auteur” among screen writers, Towne managed to bring to the screen a highly personal and influential vision of Los Angeles.

“It’s a city that’s very elusive,” Towne said in an interview with The Associated Press in 2006. “It’s the westernmost part of America. It’s kind of the last resort. It’s a place where, in a word, people go to make their dreams come true. And they’re always disappointed.”

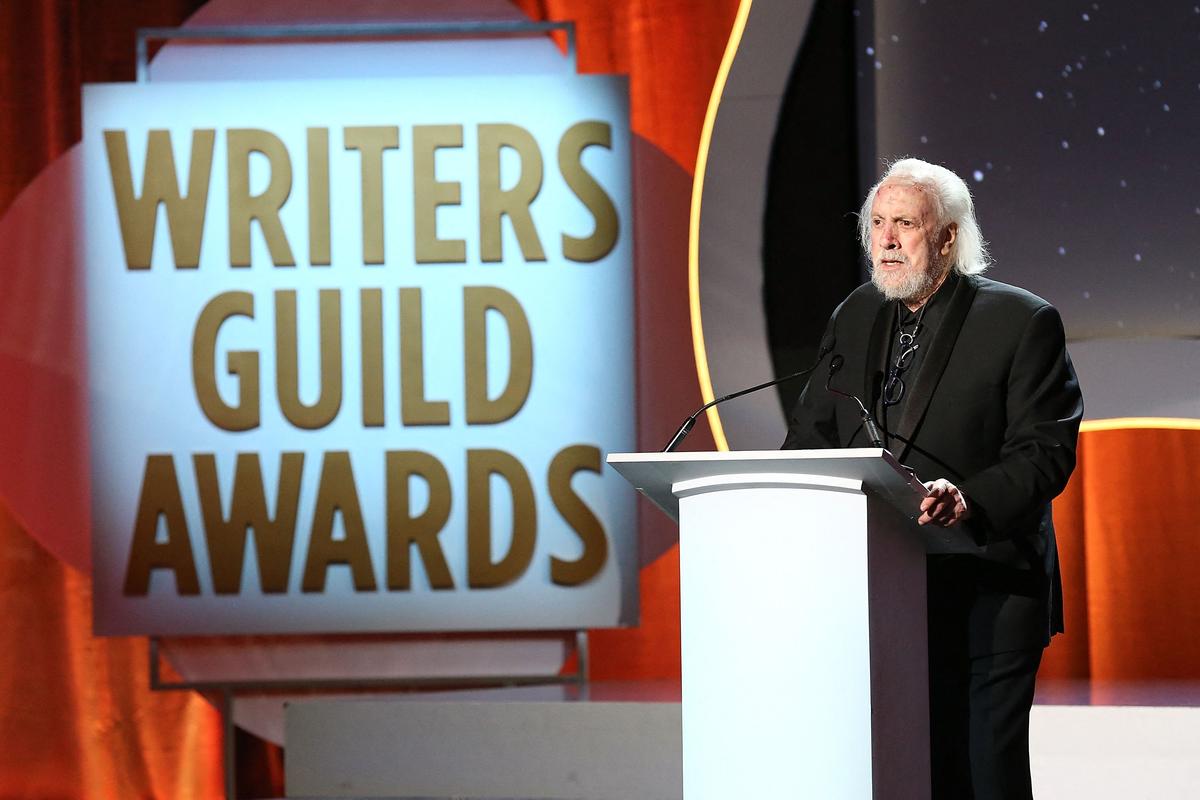

Towne, known in Hollywood for his high forehead and bushy beard, won an Academy Award for “Chinatown” and was nominated three times for “The Last Detail,” “Shampoo” and “Greystoke.” In 1997 he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Writers Guild of America.

“His life, like the characters he created, was incisive, iconoclastic and totally (original),” “Shampoo” actor Lee Grant said on Axe.

Towne’s success came after a long stint working in television, including “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” and “The Lloyd Bridges Show,” and low-budget movies for “B” producer Roger Corman. In a classic show business story, he owes his success partly to his psychiatrist, through whom he met Beatty, a fellow patient. When Beatty was working on “Bonnie and Clyde,” he called Towne in to revise the Robert Benton-David Newman script and kept him on the set while the film was being shot in Texas.

(Files) Writer/Director Robert Towne speaks onstage during the 2016 Writers Guild Awards LA ceremony at the Hyatt Regency Century Plaza on February 13, 2016 in Los Angeles, California | Photo Credit: Philip Faraone

Towne’s contributions to the landmark crime film “Bonnie and Clyde,” released in 1967, were uncredited, and for many years he was a favorite ghostwriter. He helped on such films as “The Godfather,” “The Parallax View” and “Heaven Can Wait,” and referred to himself as “a relief pitcher who could come in for an inning, not pitch an entire game.” But Towne was credited by name for Nicholson’s macho film “The Last Detail” and Beatty’s sex comedy “Shampoo,” and was immortalized by the 1974 thriller “Chinatown,” set during the Great Depression.

“Chinatown” was directed by Roman Polanski and starred Nicholson as J.J. “Jake” Gittes, a private detective asked to pursue the husband of Evelyn Mulwray (played by Faye Dunaway). The husband is the chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, and Gittes finds himself caught in a chaotic cycle of corruption and violence, personified by Evelyn’s ruthless father, Noah Cross (John Huston).

Influenced by the imagination of Raymond Chandler, Towne revives the menace and mood of classic Los Angeles film noir, but molds Gittes’ labyrinthine journey into a grander and more insidious portrait of Southern California. The clues accumulate in a timeless detective story, and lead inexorably to tragedy, summarized by one of the most repeated lines in film history, words of grim fatalism that a devastated Gittes receives from his partner Lawrence Walsh (Joe Mantell): “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.”

Towne’s script has been a staple of film writing classes ever since, though it’s also a lesson in how movies are often made and the risks of crediting any one film to a single perspective. He acknowledged working closely with Polanski as they revised and strengthened the story and fiercely arguing with the director over the film’s bleak ending — an ending that Polanski insisted on and Towne later agreed was the right choice (no one has ever been officially credited with writing “Forget It, Jake, It’s Chinatown”).

But the concept originated with Towne, who turned down the chance to adapt “The Great Gatsby” for the screen so he could work on “Chinatown,” which was inspired in part by Carey McWilliams’ book, “Southern California: An Island on the Land,” published in 1946.

“There was a chapter in it called ‘Water, Water, Water,’ which was a revelation for me. And I thought ‘Why not make a film that’s about crime and that’s out in the open,'” he told The Hollywood Reporter in 2009.

“Instead of a jewel-encrusted hawk, make it something as common as a water faucet, and make a plot out of it. And when I read about what they were doing, throwing out the water and starving the peasants off their land, I realised the visual and dramatic possibilities were huge.”

The back story of “Chinatown” has become a kind of detective story in its own right, explored in producer Robert Evans’ memoir, “The Kid Stays in the Picture”; in Peter Biskind’s “East Riders, Raging Bulls,” a history of 1960s-1970s Hollywood; and in Sam Wasson’s “The Big Goodbye,” a book entirely devoted to “Chinatown.” In “The Big Goodbye,” published in 2020, Wasson alleged that Towne was assisted extensively by a ghostwriter — former college roommate Edward Taylor. According to “The Big Goodbye,” for which Towne declined to be interviewed, Taylor did not seek credit in the film because his “friendship with Robert” mattered more.

Wasson also wrote that the film’s famous closing line was taken from a deputy police officer who told Towne that crimes in Chinatown were seldom prosecuted.

“Robert Towne once said that Chinatown is a state of mind,” Wasson wrote. “Not just a spot on a map in Los Angeles, but a state of total awareness that is almost indistinguishable from blindness. To dream you’re in heaven and wake up in the dark – that’s Chinatown. To think you’ve got it all figured out and then realize you’re dead – that’s Chinatown.”

After the mid-1970s the studios gained more power and Towne’s reputation declined. His own attempts at directing, including “Personal Best” and “Tequila Sunrise,” yielded mixed results. “The Two Jakes,” the long-awaited sequel to “Chinatown,” was a commercial and critical disappointment upon its release in 1990 and caused a temporary estrangement between Towne and Nicholson.

Around the same time, he agreed to work on a film far removed from the art-house aspirations of the ’70s, the Don Simpson-Jerry Bruckheimer production “Days of Thunder,” starring Tom Cruise as a race car driver and Robert Duvall as his crew chief. The 1990 film was famously over budget and mostly panned, though its fans include Quentin Tarantino and countless racing fans. And Towne’s script popularized an expression used by Duvall when Cruise complained that the other car hit him: “He didn’t hit you, he didn’t bump you, he didn’t push you. He rubbed you.”

“And Robin, son, is raisin.”

Towne later worked with Cruise on “The Firm” and the first two “Mission: Impossible” films. His most recent film was “Ask the Dust,” a Los Angeles tale he wrote and directed and which was released in 2006. Towne married twice, the second time to Louisa Gaul, and had two children. His brother, Roger Towne, also wrote screenplays; his credits include “The Natural.”

Towne was born Robert Bertram Schwartz in Los Angeles and moved to San Pedro after his father’s business, a dress shop, closed during the Great Depression. (His father changed the family name to Towne). He had always been interested in writing, and his proximity to the Warner Bros. Theatre and reading critic James Agee inspired him to work in films. For a time, Towne worked on a tuna boat and often spoke of its impact.

“I’ve combined fishing with writing in my mind to the extent that each script is like a journey that you’re on — and you’re fishing,” he told the Writers Guild Association in 2013. “Sometimes both of those involve an act of faith … Sometimes it’s just pure faith that keeps you going, because you think, ‘God damn it, nothing — not even a morsel today. Nothing is happening.'”