Shounak Sen remembers sitting in his car in a traffic jam one day when the sky was grey and hazy and noticing black kites flying in the distance. “I clearly felt like I saw one of those black dots falling down,” the award-winning Indian filmmaker and video artist said in a discussion during Science Gallery Bengaluru’s Carbon Film Festival in Bengaluru recently.

Shaunak Sen | Photo Credit: Chris Pizzello

Overwhelmed with the idea of what happens to a bird that falls from a polluted sky, he pulled out his phone and searched Google. That’s when he first learned of two brothers, Saud and Nadeem, who would become the subjects of his 2022 documentary film. all that breathesWhich was also screened in the film festival.

He told nature educator and conservationist Garima Bhatia and wildlife biologist and conservation scientist Ravi Chellam, with whom he was interacting in the session, “I messaged them on Facebook on a whim and then went to meet them.”

This, in many ways, was the starting point for this beautiful film, which won several international awards, including the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival and the Golden Eye at the Cannes Film Festival in 2022, and was also nominated for the 95th Academy Awards in the Best Documentary Feature category.

Set in Delhi, the film tells the story of two brothers (and their assistant, the very charming Saliq) who are former bodybuilders and who have dedicated their lives to saving and curing birds, particularly black kites. But it is also a portrait of a city and its inhabitants – both human and non-human – living through turbulent times, and a meditation on the relationship between humanity and the other living creatures with whom we share this world.

During the discussion, Shaunak also talked about how the film was shaped by the people he met during his fellowship at Cambridge. “I was around people working on human-non-human relationships… someone was working on wolves in Chernobyl, someone was working on vegetation in Fukushima,” he says. This led him to think about a more-than-human perspective that “doesn’t see humans as an absolute reference point but as a kind of relational entanglement between human and non-human species,” he adds.

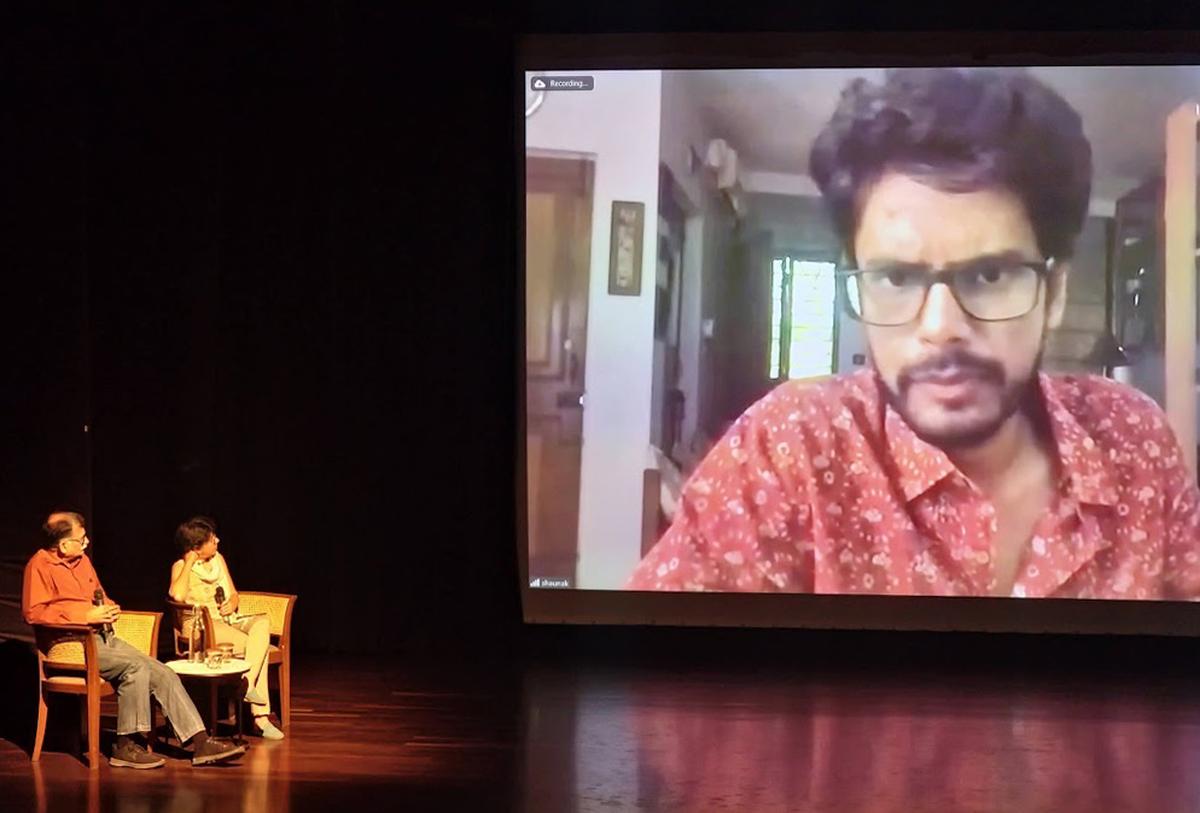

A discussion on the film ‘All That Breathes’ | Photo Credit: Handout Email

Title negotiations

Garima begins the conversation by talking about how the film made her feel, which she has already seen three times. “Each time I uncover different layers. It is always an extremely emotional experience,” she said. Ravi, who has seen the film four times, agrees. Ravi then goes on to explain the nuances of the film, starting with its title.

Shaunak says the title derives from something the brothers’ mother often told him: that you can’t create hierarchies between different life forms. “If anyone else had said that, I would have dismissed it as a big nonsense,” he says. But he says the brothers themselves live their lives by this adage.

He describes them as contemplative and meditative people who have spent much of their lives thinking about this kind of oneness, “a kinship, an entanglement between human and non-human species. I wanted a title that could capture that broad kind of neighborliness.”

A scene from the film | Photo credit: Handout Email

Shooting process

Garima Call all that breathes It is a deeply contemplative film, with a lyrical, poetic quality that forces the viewer to slow down. Shaunak says he began shooting it like any other documentary, using a handheld camera to capture his various subjects. “I had the camera in my hand and I took a raw, dirty approach,” he says. “There, the logic is that if a character moves, the camera just follows him.”

Within four or five months of shooting in this style, he realized that the material he had collected was too restless and intense. “This style helps when you want really raw images, whether it’s with action or deeply immersed characters,” he says. “But my characters weren’t restless. They were very quiet and contemplative; that was their vibe.”

Therefore, he concluded that he needed to find a different way to tell this story so that the form and content could match each other. “Gradually I realised that to tell this non-fiction story I would have to play with the tools of fiction,” he says, adding that he wanted the film to have the outer shell of a fiction film, even though its heart remained non-fiction. “That’s how the form came about,” he says.

a question of time

Indeed, like any good work of fiction, all that breathes There’s a lot to it. The lives and struggles of its brilliantly crafted characters achieve a certain universality, asking big questions about the human condition: identity, belonging, love and meaning. “I realised that Bhai was really intelligent and philosophical. I wanted a form that would allow him to speak his smartest thoughts,” says Shaunak, who interspersed voiceovers of these thoughts within the narrative.

He said the voiceover form gave him a chance to access the past and learn how he started this life “where it felt like a love story about two brothers and a bird … this fascinating otherworldly bird that looks like an alien with glass, reptilian eyes.”

He also talks about the film’s use of long takes, its essayistic style of shooting, which makes it more creative than a journalistic documentary, and the actual shooting process, which he describes as “essentially ornithological.” Like watching birds, he says you must slow down, slow down and minimize yourself when shooting. “You’re just receding into the wallpaper … trying to gather some fragments of everyday life.”

According to Shaunak, getting a feel of everyday life, “content steeped in ordinary mundanity”, is primarily a question of timing for documentary filmmaking. “The first month is usually a waste because everyone is so self-conscious and awkward,” he says. But if one continues shooting, a sense of normality and reality starts to set in. “Everything is as raw and as unblemished as it can be,” he says. “Rest is really just a function of pure timing… letting the camera run for three years.”

Other discussions

Other aspects discussed in the session included how the publicity changed the life trajectory of these brothers, the originality of the footage, why the film was not released in theatres in India, the politics of the film and the challenges of shooting it during Covid-19.

Shaunak explains how the film took on a life of its own that was absolutely phenomenal, especially when it was nominated for an Oscar. He also made sure the brothers were a part of every major event associated with it. “Nadeem has probably been to more film festivals than me,” he says, adding that the media spotlight meant they received a lot of donations. He also feels it would be foolish for him to think a film could change the brothers’ lives. “I hope it provides a momentary oasis and a kind of witness to their unique lives,” he says.

Film as a Trojan Horse

He also believes that films can be like a Trojan horse, helping people have conversations they might not necessarily want to have in a subtle way. “You sneak into the conversation and affect people emotionally without being pedantic.” This is why, he says, he doesn’t like many wildlife documentaries which are often preachy and pedantic, making people feel bad about themselves. “It actually does more harm than good.” Instead, he believes in what he calls little empathy plugs. “That’s usually how films work. They enter the cultural bloodstream and amplify a set of ideas that we’re all trying to push forward”.