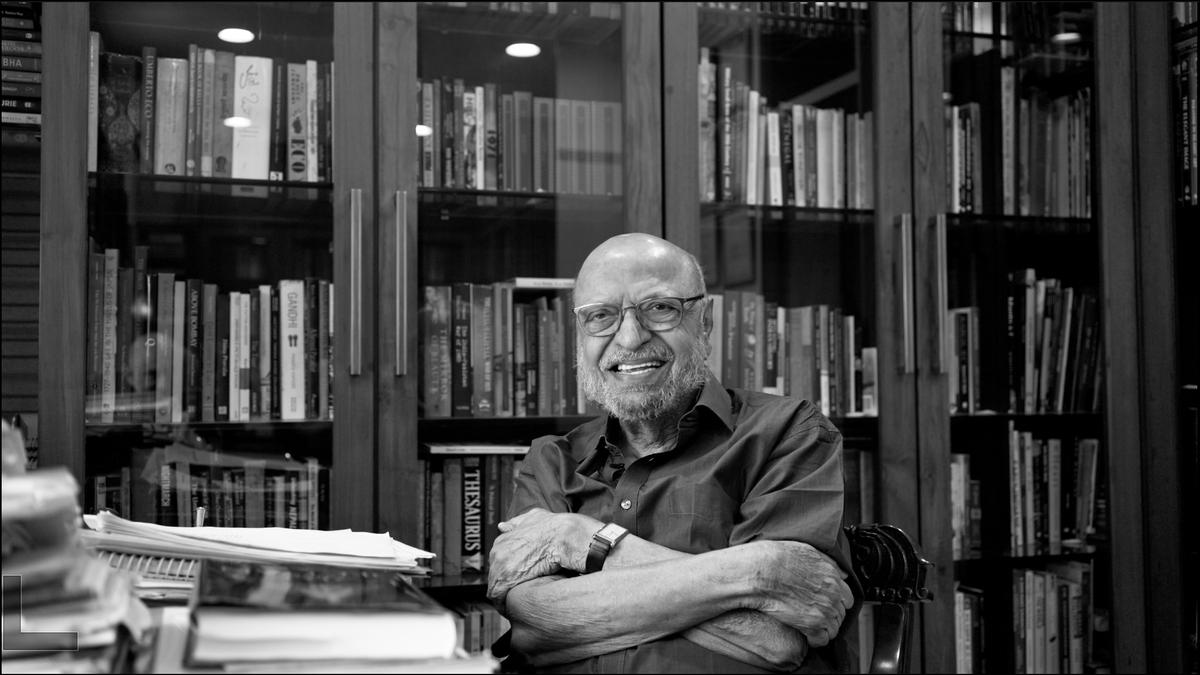

Forty-four years after knowing and working with Shyam Benegal, I finally turned my camera on him. It was January 2023.

I was asking him about his movie Market (1984), on which I also worked.

One of my jobs at that time was to photograph the actors’ costumes, make-up and jewellery. Market Was in color but we didn’t have the budget for a Polaroid camera. So I was handed a camera with a few rolls of black-and-white film.

Those photographs remained lying in a box for 40 years. Post-pandemic, after moving house and sorting through boxes, I rediscovered them. And thought of making a film on photographs and memories.

(L-R) Shyam Benegal, Dev Benegal, and Satyajit Ray on the set of the documentary Satyajit Ray

When we met in January, Shyam had said, “I haven’t talked about or discussed the film for many years… the memories have become blurry.” As my camera panned, He talked about its genesis, filming and even its reception. By then he had become quite unwell. Still his memory was very sharp.

“It worked well because of the actors. They were part of the creative side of the film… not just their performances, but they all contributed to the story. The film stars Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah among others.

Shyam was always an accomplished director, he never took credit for the world and characters he created. There was no arrogant ego in him. His filmmaking style was always collaborative. He encouraged constant questioning of his actors.

This openness and collaboration was the biggest lesson for any young filmmaker.

Unveiling the second India

after ten years of working MarketI made my first feature, English, AugustAfter its screening, in the lobby of Metro Cinema, Shyam said, “I was nervous when it started. I was wondering how you carried that style through the film. And then, to my relief, he smiled.

Shyam Benegal Photo Credit: Dev Benegal

Market It was satire; In its jazzy, loose style, it was a searing indictment of society and its antiquated morals. Based on a true incident – when Motilal Nehru was running the municipal corporation in Allahabad – it was set in a fictional city, like the fictional city of Madna in my film. English, August,

i worked on it Kalyug (1981), Ascent (1982), Market (1983), and Satyajit Ray (1984) with Shyam. Working with him and his colleagues was a greater education in every aspect of cinema than any formal class could ever be. Ashok Mehta, Shyama Zaidi, Satyadev Dubey, Kamat Ghanekar, Bhanudas Diwakar, PG Mule, Vanraj Bhatia… the list is endless.

His office, Shyam Benegal Sahyadri Films or SBSF as we called it, was making commercials as well as feature films every year, which kept the atmosphere alive.

What set him apart was his breadth of knowledge. There was almost no subject in which he did not have deep insight or original viewpoint. He was truly a renaissance man.

He never believed in the industrial way of film making, being fragmented and divided. Instead, he encouraged us to work on every aspect of it. He was always walking that tightrope; I want to engage the audience, while also experimenting fearlessly with form. Cinema as a medium was almost infinitely flexible for him.

Through his films, Shyam unveiled another India. His films were not entertainment. They were determined to be visceral, raw and uncomfortable. Power, politics, gender, caste – these were their areas of engagement. For him film was part of the process of social reconstruction. You can’t deny the uncomfortable realities of his film world. He exposed inconvenient truths, the harsh realities of contemporary India, especially an India that seemed to him to be derailing.

Very few people understand the language of cinema as well as him. He spoke through his films, and the thread that runs through his work is that filmmaking is, first and foremost, an act of social responsibility. We must not forget: he was a young man of 15 at the time of India’s independence and the new idea of an independent, democratic and secular country was as fundamental to him as it was to others of his generation. It was creative.

Undoubtedly a Nehruvian optimist, he believed that cinema, more than any other art form, could express the idea of a complex, pluralistic nation – just as Jawaharlal Nehru described it as “the ancient inscription upon which thought and reverence It was described as “inscribed layer by layer”. , In his understanding, cinema was of a great scale, completely democratic and uniquely accessible across all geographical regions and cultures. In the darkness of the cinema hall, everyone is equal.

For this reason, censorship worried him. He could never digest the idea that a handful of people could decide what the rest of the country should see. When we were preparing a film to submit to the censor board, he used to say, “Let people decide what they want to see.”

easy banter and camaraderie

New York was his and (wife) Neera’s favorite city. Our times there were special. We’d get out of some unbearable ceremony at a film festival, and I’d take her to a little dumpling restaurant in Chinatown. Friends also joined. The conversation continued till late night. That’s what he loved most: the conversation and spontaneous laughter and camaraderie of people bound by art.

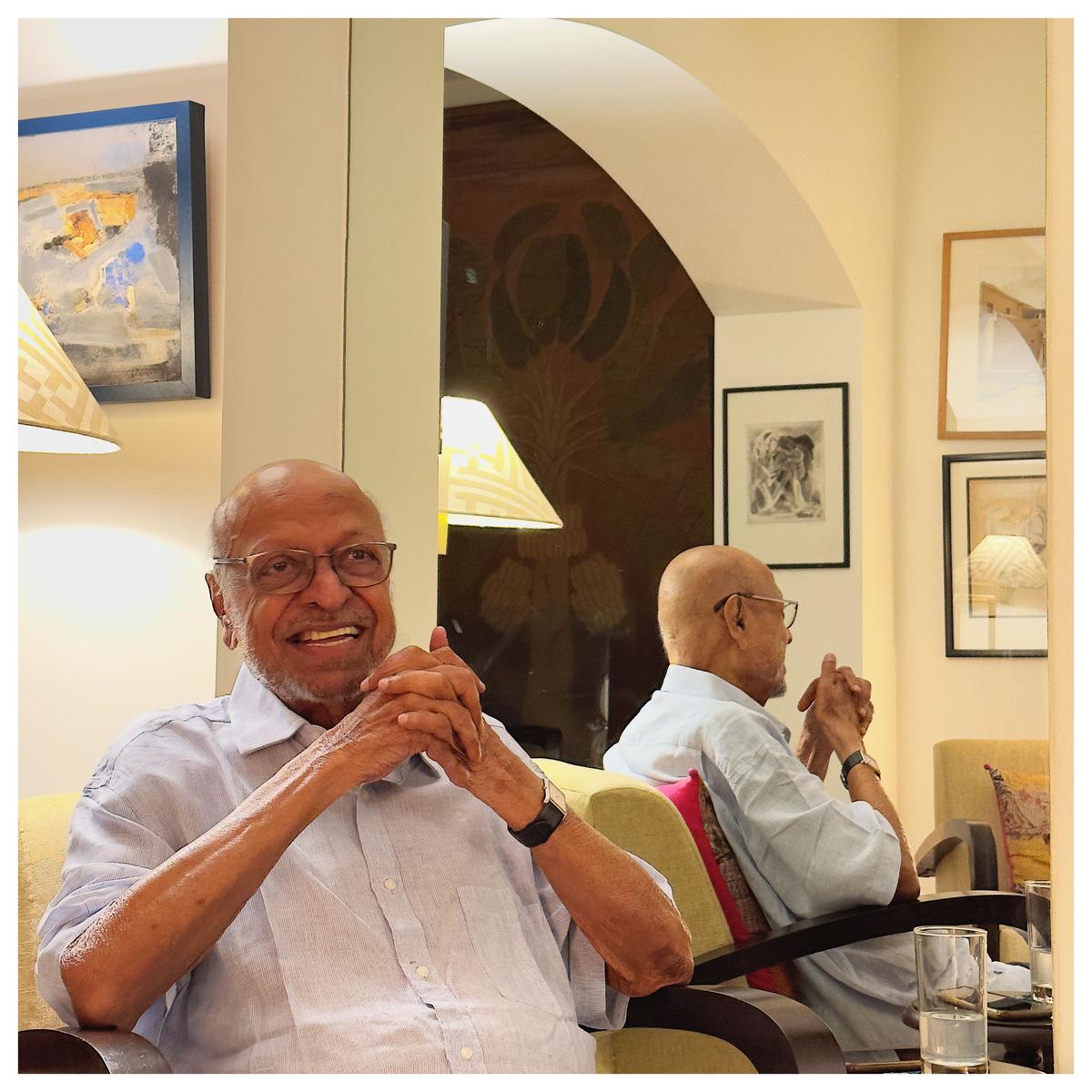

The last few years were very intimate. The four of us – Shyam, Neera, their daughter Piya and I – used to meet together in the evening. What was planned for one hour will extend to five hours. Again, laughter was at its core.

(L-R) Shyam Benegal, Pia, Neera and Dev Benegal

In 1982, the film division asked him to make one film on Nehru and another on Satyajit Ray. Shyam asked in which film I would like to work. Without a moment’s hesitation, I chose the latter. It took longer than expected to make a film on Satyajit Ray. I was working for Girish Karnad in London CelebrationJennifer was ill and Shashi Kapoor asked if I could stay and work on the subtitles 36 Chowringhee LaneI couldn’t say no. When I finally returned to India, Shyam called and said that Ray’s film was not completed. He was waiting for me to return to work.

I came inside immediately. There were several hours of 35 mm film rolls to edit. From research, being present on the set while we were filming, looking under the producers’ beds to find the negatives of Ray’s films, to the final sound mix, color-grade and delivery of the prints – it was completely Was done by hand. I had a huge responsibility and at times I wondered whether I would be able to live up to Shyam’s standards.

When we finally got the VHS of the film, Shyam took my copy and wrote a beautiful inscription on the label. It read: “This film is as much yours as it is mine.”

I am not alone in this thinking. Filmmakers and film audiences in India carry a bit of Shyam’s world with them wherever they go. Beyond his art, he showed us the value of making moral choices. There are lasting lessons and inspirations in his work, and the way he chose to work, for artists everywhere, and yes, the inspiration activists need to stand strong against the wrong tide.

But the thing is: the mark of a truly great artist is generosity – of spirit, of time, of teaching, of friendship. Shyam was a friend and mentor from first to last who kept on giving. He will be with us for the rest of our days.

The author is an award-winning filmmaker, known for English, Augusthis film still Life On Shyam Benegal and his memory Market Will be out this year.

published – January 03, 2025 10:52 am IST