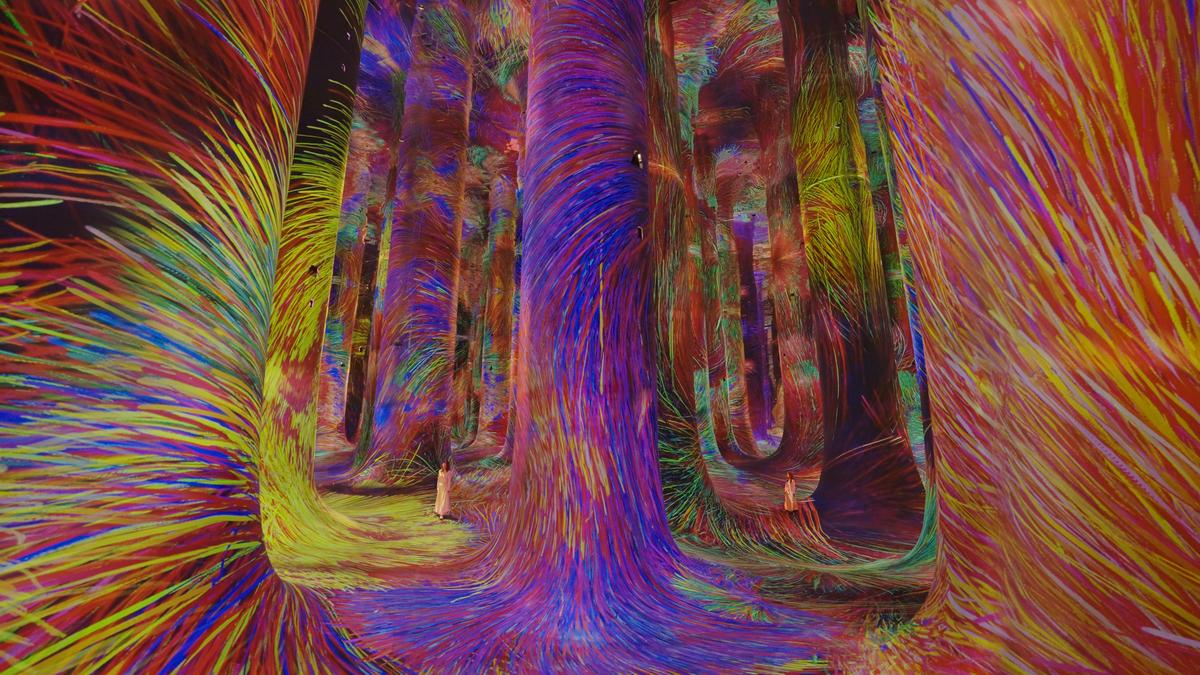

Since its founding in Tokyo in 2001 by engineer and technologist Toshiyuki Inoko, TeamLab has grown from a small group of friends experimenting with code and light to become one of the best-known groups of artists working with technology today. Known for creating large-scale immersive environments – waterfalls that respond to touch, forests that glow and fade, fields of light that seem to breathe, and gardens that bloom and dissolve – TeamLab’s work subtly, playfully, highlights the joy of being one with the world.

For years, the art world didn’t know what to make of them. TeamLab’s communications director, Takashi Kudo, recalled the early days in an interview with Asia Society, saying: “As time went on, while we gained an enthusiastic following among young people, we were still ignored by the Japanese art world. Our debut finally took place in 2011 at the Kaikai Kiki Gallery in Taipei, thanks to artist Takashi Murakami.”

Takashi Kudo, Director of Communications, TeamLab | Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

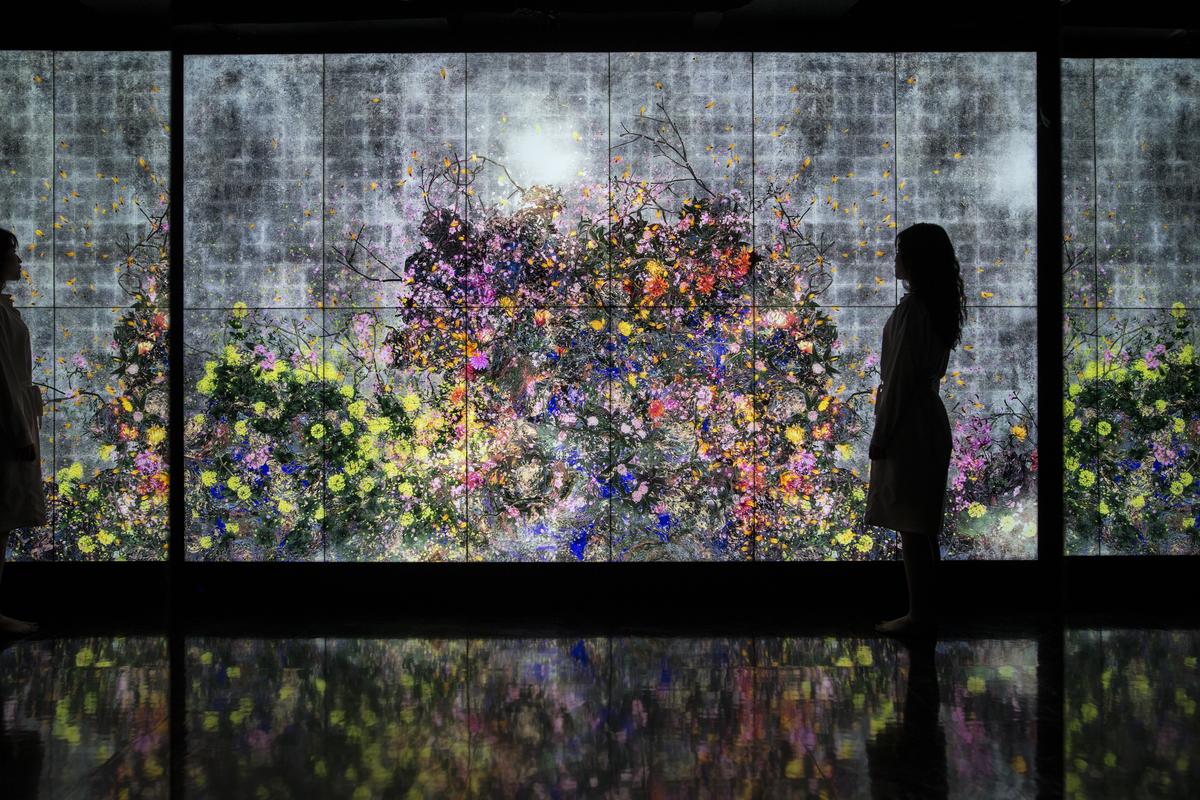

Since then, TeamLab has developed its own language, creating museums and installations that attract millions of people around the world. Among them are TeamLab Planets in Tokyo, where visitors wander through gardens featuring water and mirrors, and TeamLab Borderless, a “museum without a map” where artworks flow seamlessly into the rooms. In San Francisco, TeamLab: Continuity expands the Museum of Asian Art into a vibrant world of flowers and fishes. And in Abu Dhabi, TeamLab Phenomena – the group’s most ambitious project to date – merges architecture, art and nature into an evolving experience, bringing their vision closer to India than ever.

A forest and spiral of echoing lamps. Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

Kudo to be in conversation with Asia Society India Center ahead of Art Mumbai this month in Mumbai – just a few years after the collective won the Asia Society Asia Arts Award in 2017. Edited excerpts.

I know that when I talk to you, I am not talking to one person but to a whole group. So, who is TeamLab?

TeamLab is an art collective. The word ‘team’ is important: everything we do is a collaborative process. At our core, we are always doing research, not in the academic sense, but to understand how humans perceive and engage with the world, how people understand their ‘existence’.

Who is part of the collective?

In other words, we are like a flock of birds or a school of fish, each member moves independently, but together we create a collective movement. There are no leaders here, it’s all organic. Every project attracts the people it needs: software engineers, architects, mathematicians, animators, graphic artists, musicians, writers, coders, etc. Some people join for fun, some for growth, some for money. Everyone has their reason. At any given time, depending on the project, around 200–300 people are involved. The collective continues to expand and develop.

Order in chaos Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

Megaliths in the bathhouse ruins Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

Given how much of your work uses technology, is there still an analog, non-digital side to your process?

Absolutely. The creative process always involves trial and error, prototyping, failures, arguments. Each member solves the problem with his expertise. And yes, we argue – in the most humane, tailored way. Those arguments are part of our creative process. They make the work stronger.

Your work is often described as “immersive”. Why do you think people today need to step inside something to feel it?

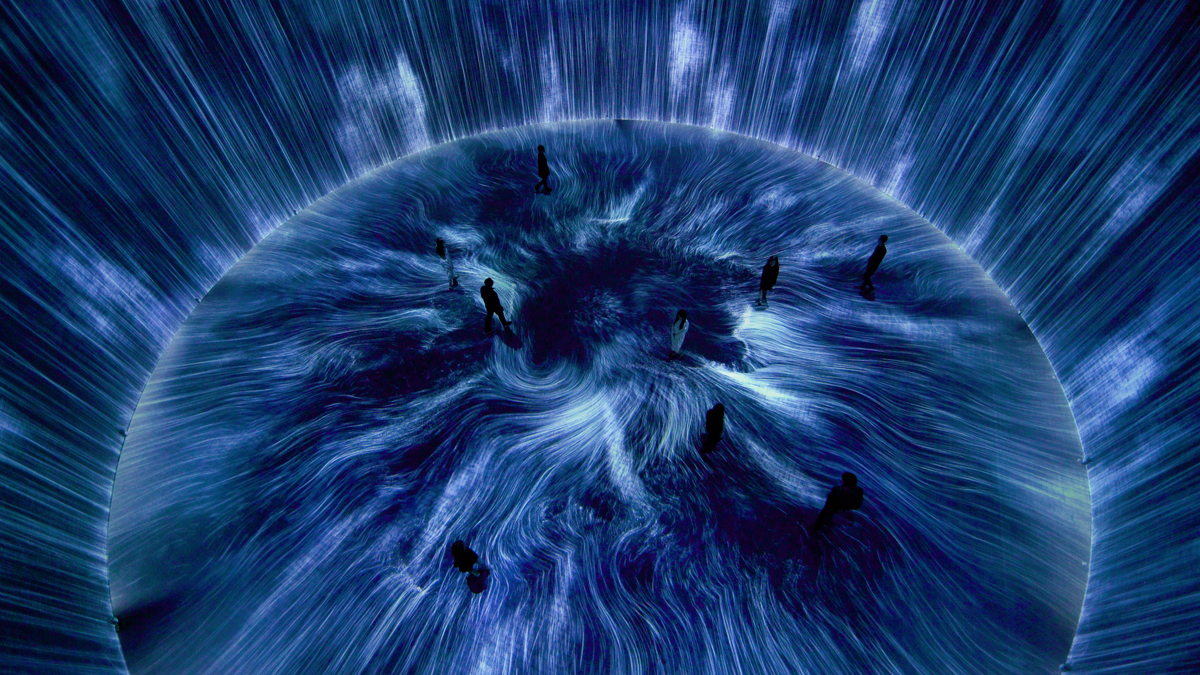

Nature itself is immeasurable. When you climb a mountain, walk for hours, and finally see the sunrise – that moment of exhaustion and awe – you feel like you are part of the world. Through our installations, we want people to feel physically connected, not just observing the art but becoming a part of it. Today, most people consume the world through screens. But true understanding is physical, like learning to swim. You can read about it or watch videos, but until you jump in the water, you’ll never know what it means. Art should also enter with the body.

In our installations, people become part of the artwork, like entering a digital garden or forest. Work is alive and changing. This is nothing new, it is a continuation of something ancient. People call it immersive, but that’s how the world has always been for us.

Where does technology fit into the relationship between body and world?

Technology is merely a material, just as paint or clay once was. For centuries, artists used [all] The tools available to express their imagination. Today, our tools are projectors, sensors and software but technology is not the goal. It is a medium through which we create experiences that expand our perception of the world.

Everlasting Life and Death II | Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

And yet your work continues to circulate among public spaces, including galleries, museums, parks. How has your relationship with the “art world” evolved through all this?

When we started, the art world didn’t take us seriously. This changed with time. But our belief remains: only art can change the way people think and live. Design, law, politics, they provide the answers. On the other hand, art asks new questions. And when society changes, the old answers stop working. The Industrial Revolution gave us a set of ‘right answers’. The digital revolution requires the new. Art helps us explore those questions.

And ultimately, while we do what we must do to make ends meet and survive, for us, art is not about ownership or names. If our work changes the way people think, or how they engage with the world, that’s enough.

The universe of water particles in the tank, transcending boundaries. Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

The universe of water particles in the tank, transcending boundaries. Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

You often talk about the continuity between humans, nature and technology. I sense some spirituality in it. How does Buddhism or Japanese philosophy shape this worldview?

We were born in Japan, so those influences are natural. Buddhism, Shintoism, the sense of continuity between things, it’s in our culture. We are interested in reconstructing what our ancestors expressed using today’s technologies. Japanese art has always been spatial: think of sliding doors, gardens, the way light moves through space. These forms were influenced by the cultures of the Silk Road from India to Persia and Japan. That kind of art disappeared in the 19th and 20th centuries because it was not compatible with industrial modernity. But with digital technology we can bring back that sensitivity.

In our installations, people become part of the artwork, like entering a digital garden or forest. Work is alive and changing. This is nothing new, it is a continuation of something ancient. People call it immersive, but that’s how the world has always been for us.

The floating flower garden, the flower and I are from the same root, the garden and I are one. Photo Credit: Courtesy TeamLab

This cyclical idea that technology can return us to something ancient feels particularly resonant in India. Before we wrap up, what would you like to say to the audience here?

Let me tell you a small story. In 1996 or 1997, I was traveling in India as a university student, living like a backpacker. Every morning, I would drink juice from a fruit seller in the market. One morning, I asked for apple juice. He smiled and gave me mango juice in return. I told her again, “No, I want apple juice.” He nodded, said he understood and gave me another mango juice. I was confused but drank it anyway. It was sweet, fresh and perfect. Later I realized, he wasn’t ignoring me. He understood that the best fruit that morning was mango. He wanted to give me the best thing he could. That moment changed the way I think about care, misunderstandings, friendship, and perhaps even how to make art.

Takashi Kudo will be in conversation with Pratik Raja, Director of Experimenter, as part of the third edition of Asia Society India Centre’s Trailblazer series on November 9 at IF.BE, Mumbai.

Culture writer and editor specializing in reporting on art, design and architecture.