Mansukhbhai Pitambar Khatri, the last custodian Bella Printing in Kutch | Photo courtesy: Special arrangement

April 30, AjrakhThe famous resist dyeing craft of Kutch has received the Geographical Indication (GI) tag, a mark of authenticity that provides legal protection to arts from specific geographical regions. While this is cause for celebration, another lesser-known craft — Bella Block printing – from the same region, languishing in oblivion.

At one time, Bela village, located in Rapar block of Kutch in Gujarat, was a flourishing centre of the block printing trade. In undivided India, Bela was full of traders and camel trains that carried people between Kutch and Sindh in present-day Pakistan. For the craftsmen Bella The business of block printing on cloth was doing well. Things have changed dramatically in the last few years and today this art is in danger of vanishing completely, but this would not have been possible without the efforts of its sole custodian Mansukh Pitambar Khatri.

gradual decline

Mansukhbhai, now in his late 50s, was just eight when he first learnt to make graphic prints on cloth using organic colours and carved wooden blocks. As a child, he and his elder brother would sit and watch their father work hard. “All the family members would be involved in the printing process – washing, printing, dyeing,” he recalls. “I found it all very fascinating. How a plain piece of cloth turns into something so beautiful. It was because of my interest that I learnt the art.” Unfortunately, his father died when Mansukhbhai was very young and so he turned to his brother to learn the finer aspects of the art.

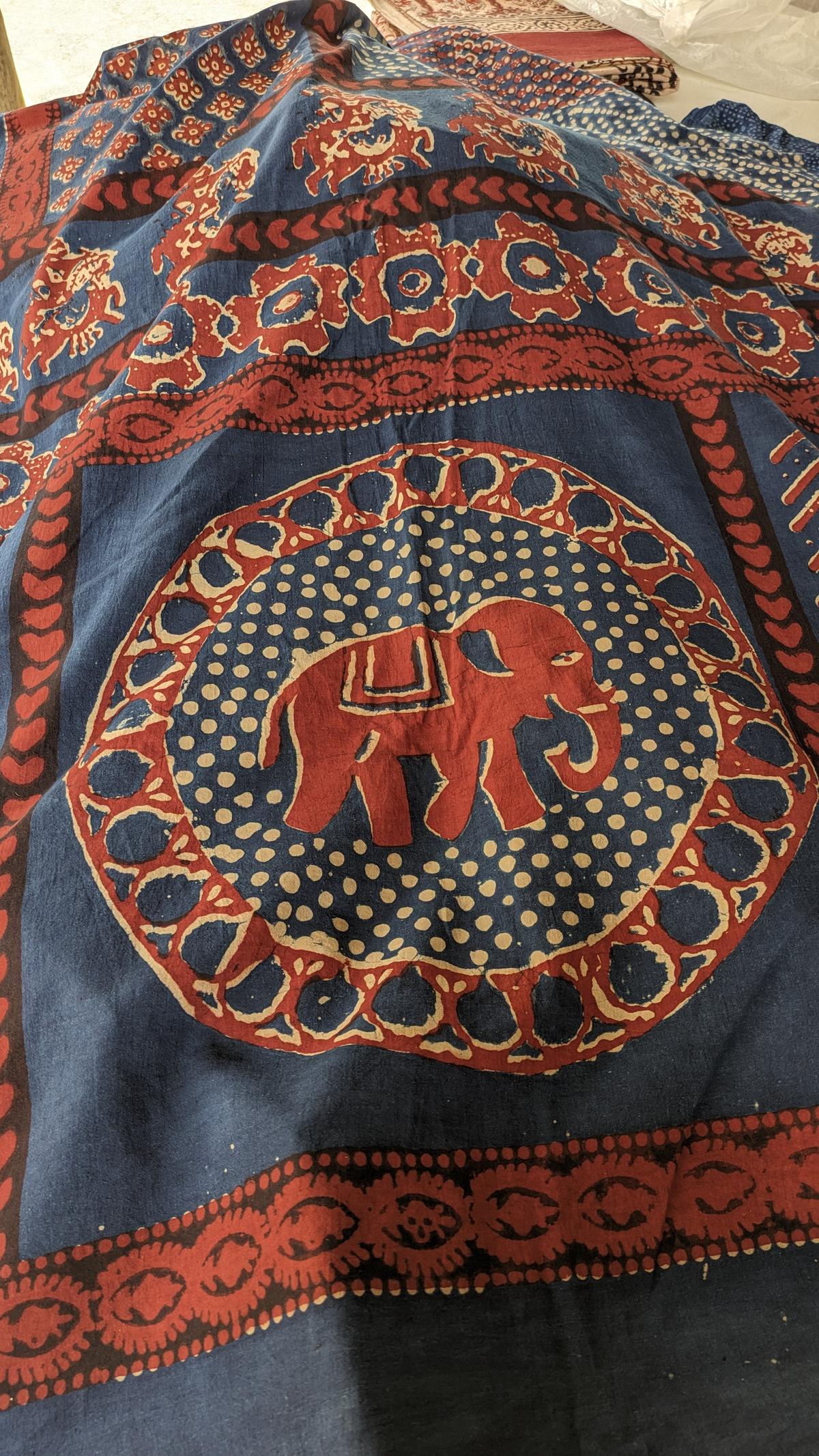

Bella Block printed fabric | Photo credit: Special arrangement

the beauty of Bella The biggest feature of the printing is its bold design. According to Mansukhbhai, Ajrakh It’s all about thin lines and mostly geometric or floral designs, Bella It includes thick lines, including animals such as elephants and horses. “There is a difference in the process as well,” he says. “The resistance that occurs Ajrakh A mixture of lime and glue is used; Bella we use Soil A mixture of wax, clay and millet flour. This paste is thick.”

Several factors contributed to this BellaBesides the collapse of the border between India and Pakistan and the gradual drying up of the open trade route, there has been a decline in trade. Take, for instance, the advent of power looms and screen printing. The traditional artisans had no chance against the speed and price of these fabrics. “We had about 40-50 Khatri families who were involved in this work. Bella “Earlier we used to do printing work, now it’s just me,” says Mansukhbhai. “Also, being about 180 km away from Bhuj, we are not on the tourist map. So tourism has not helped us as much as other craft forms have.” Earlier, mostly families were involved in this. Bella People associated with the printing industry, including Manuskhabhai’s relatives, have now turned to other businesses like sweet making.

Saving blocks

Mansukhbhai too had given up the craft for a period of two years – his business with a select few traders was not meeting the family’s needs. Then around 2013, Khamir, an NGO working on preserving local crafts, persuaded him to take over the block once again. “We helped him re-learn the dyeing process, do indigo dyeing and introduce some new designs,” says Ghatit Laheru, director of Gujarat-based Khamir. “Just before Covid-19 struck, he asked for some space to do his work at Khamir itself, which we happily obliged. Now he spends most of his time here, working on both old and new designs.” Gradually, Mansukhbhai’s work found the platform it needed, with a wider audience and more demand.

The blocks that Khatri uses Bella Printing | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

“I remember throwing sacks of wood into the Saran river [river] Because there was barely any work for us,” he recalls. Showing a block with a carved figurine of a woman and a tree, he says, “I have saved a few, like this one. It was made by my grandfather and is at least 100 years old. Khamir made a longer replica of it so that my work goes faster.” Traditionally, Khatri would make different designs for different communities. For example, one community would wear prints of horses and horsemen, and another with elephants, and you could identify which community a person belonged to by his clothes. Many of these designs are now found on saris, dupattas and unstitched clothes—of horsemen, trees and elephants.

Bella It has also been listed as an endangered craft by the Office of the Development Commissioner for Handicrafts, the national agency that works for the promotion and export of Indian handicrafts, Laheru says. “This is positive news as there is now the impetus to reach out to more people through government-sponsored exhibitions and other support.”

Mansukhbhai Khatri | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Last year, Mansukhbhai’s younger son also showed interest in taking up the art. “He knows the art, but because of the circumstances, he took up a job at a shop in Bhuj. Now he is eager to return to Bela,” says Mansukhbhai, who hopes he may not be able to return. BellaAfter all, he is the ultimate guardian of the ‘.

The author is a freelance journalist based in Kutch.