MK Raina at his home in Noida. A painting by him hangs on the wall behind him. King Lear Band Pather form of Kashmiri folk theatre. | Photo courtesy: Anuj Kumar

The country that needs a hero is unhappy.” Maharaj Krishan Raina likes to adopt a quote by German playwright Bertolt Brecht in a country that indulges in hero worship. For the past several years, the veteran theatre artiste has camouflaged his perception with a gentle smile and has used culture as a catalyst for socio-political change in the most sensitive parts of the country. Be it Punjab, Kashmir or the North East, Raina says his mantra has always been, “Don’t want to be a hero”, which made his art speak.

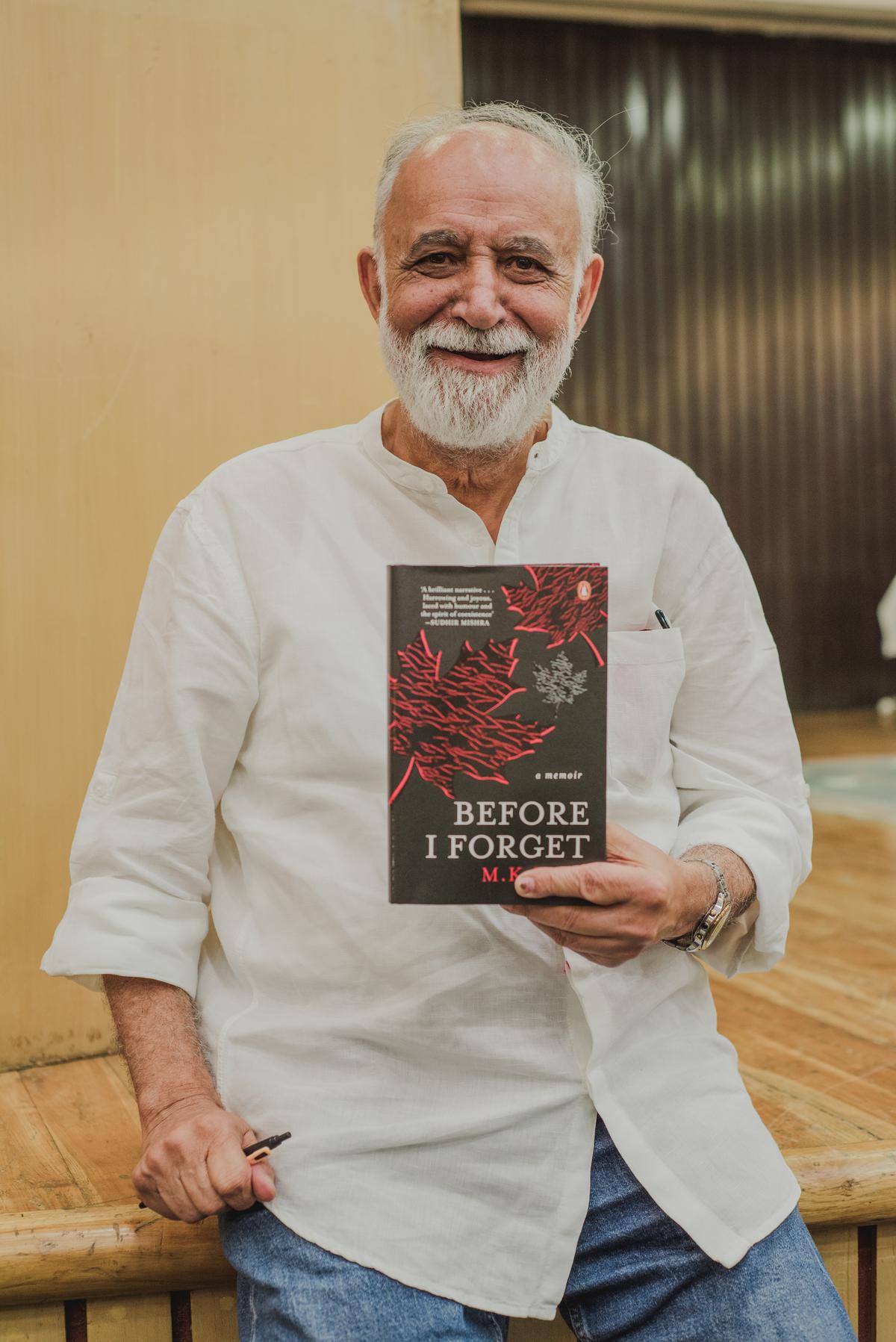

MK Raina with his memoir before I forget

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

The pandemic has given Raina the time to pause and reflect on his entrepreneurial career, and the result is an extremely readable account. before I forget (Penguin Classics), the memoir traces the historical events that shaped Raina and informed his art. From the theft of the sacred relic from the Hazratbal shrine in his hometown Srinagar in 1963, the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi, the brutal murder of cultural activist and close friend Safdar Hashmi in 1989, the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits, the fallout of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992 and the ethnic tensions in the Northeast, the memoir reads like a layered screenplay where it is impossible to take sides. No wonder his friend and director Sudhir Mishra is mulling a film script from Raina’s rich memory. This is an actor-writer-activist who, in turbulent circumstances, took his side, sometimes risking life. Taking a line from his famous play on the Oppenheimer trial, long before Christopher Nolan understood the physicist’s relevance, Raina says he doesn’t like following others’ ideas. In the Safdar case, he questioned the disruptive fascist forces and along with his friends, including actress Shabana Azmi, turned the opening ceremony of the International Indian Film Festival in Delhi into a flop show. A few years later, after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, Raina was again at the forefront, coining the slogan: Now there will be no slogans, we just have to save the country (There will be no sloganeering now, it will only be about saving the country) and questioned Atal Bihari Vajpayee. When Kashmiri Pandits were driven out of their homes, he blamed the silence of secularists for pushing the Pandits and the political narrative into the hands of the right-wing ecosystem.

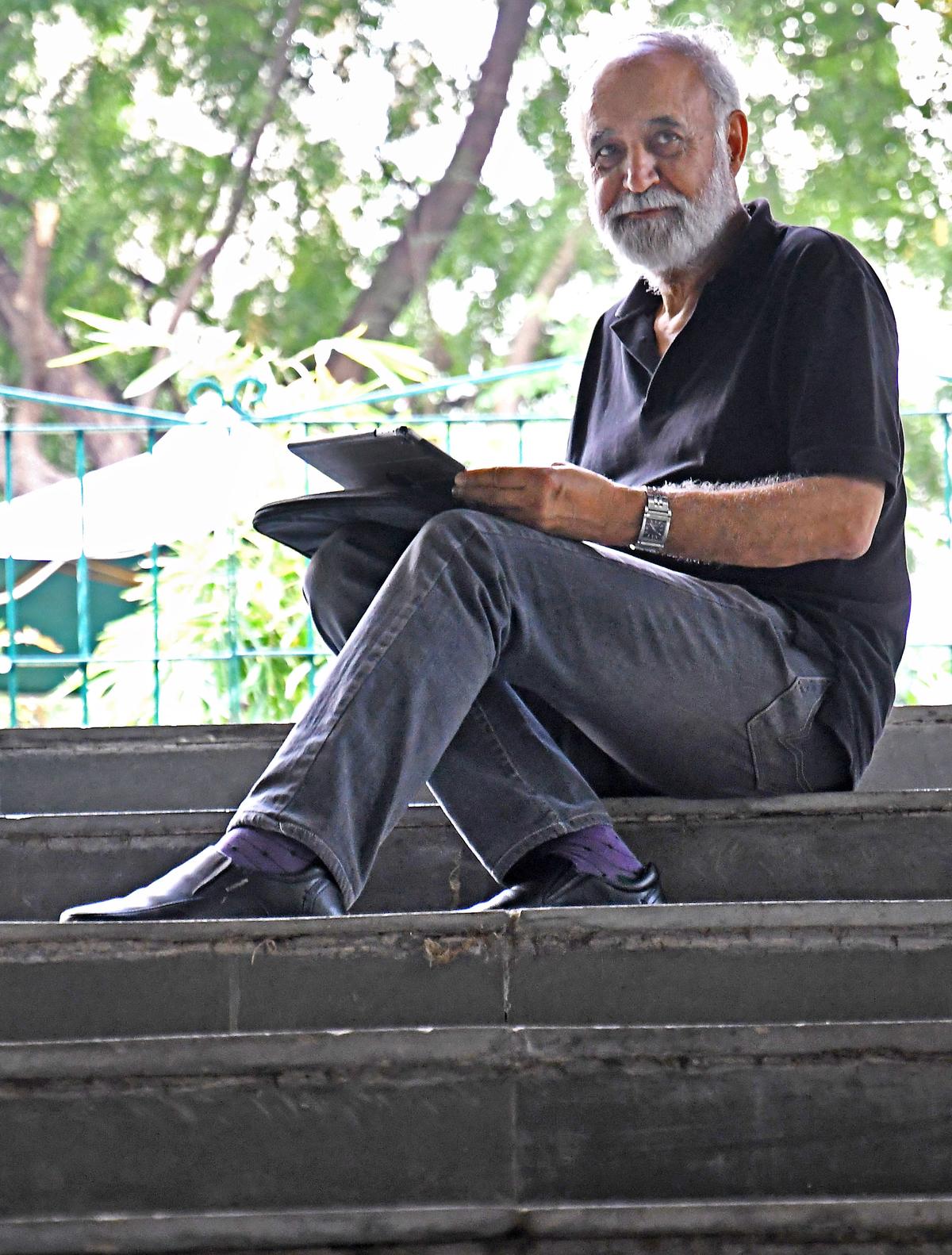

Raina has truly brought theatre to the grassroots. | Photo Credit: Sandip Saxena

“We cannot stop being citizens,” says Raina. He draws inspiration from a statue of Buddha, in which he is in deep meditation, but with one hand touching the ground. “I analyse it myself – if you stay grounded, you won’t go wrong.” Often the cure for stinging nettle is some other grass growing nearby, he says. “You just have to find it.” Inquiry is of great importance in the Indian tradition, he says. “The disciple questions the guru. It is in our Puranas. It is the essence of the Bhagavad Gita. Unfortunately, this tradition is diminishing.” Raina describes himself as a “product of socialist India”, which gave him access to lots of cheap books and the opportunity to hone his skills at the National School of Drama. “Most of us were from modest backgrounds, with a rich storehouse of tradition and no inferiority complex.” He was perhaps the first person to truly follow the aim of a theatre school: to take art to the grassroots.

From Raina’s play ‘Badshah Pather’, staged at Kalakshetra Foundation, Chennai in 2013. | Photo courtesy: Karunakaran M

Battling conservatism, Raina worked hard to revive folk theatre in the Kashmir Valley at the turn of the millennium. “I revived my ties with the villages of traditional artists spread across the region between Anantnag and Pahalgam and quietly worked with them to provide them opportunities to contribute to theatre. “We requested local potters to make masks and tailors to modify their crafts to make costumes. A trunk maker improvised to design prosthetic swords.” When the number of visitors reached 5000, the separatists came to know of Raina and his team’s presence in Pir Panjal. “They tried to thwart our efforts but by then the villagers had realised the role of culture in bringing out pent-up emotions Now you won’t even let me laugh(You won’t even let us laugh).” Raina recalls his acting career that began with Avtaar Kaul’s avant-garde film 27 Down Along with Rakhee in which he played the role of a ticket collector. Shot on a real train, Raina remembers that the authorities had to bow down to the persistence of the young team. “It was not very expensive to shoot on platforms and trains as long as you could hide the cameras. In fact, many times passengers would mistake me for a real TC. Shooting on railway stations and trains became expensive only when BR Chopra took over the responsibility of shooting on a real train. Burning Train,

Raina at the National School of Drama in New Delhi on January 14, 2012. | Photo Credit: Shiv Kumar Pushpakar

Raina worked with art cinema stalwarts like Mani Kaul and Mrinal Sen. “We were part of a movement that believed in healthy theatre and wanted to carry forward the same sensibility in cinema as well, but the movement ended when filmmakers started bringing in stars under box office pressure,” says Raina.