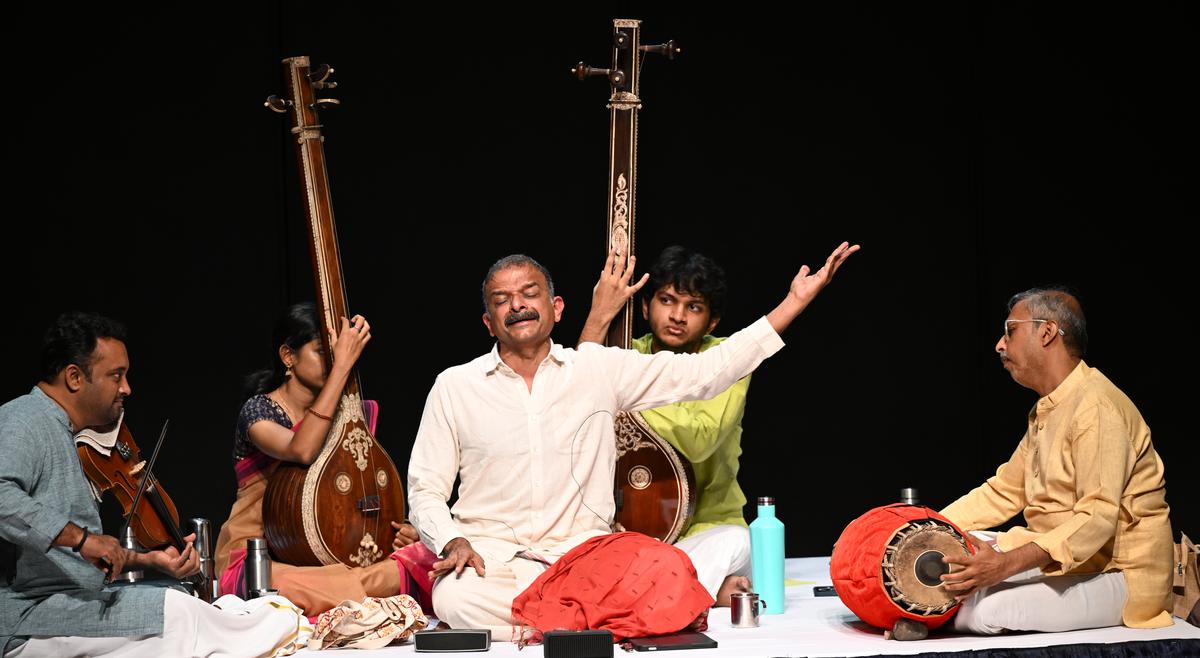

TM Krishna performing at the MS Subbulakshmi Auditorium in Chennai. | Photo courtesy: M. Srinath

Unpredictability is what makes a TM Krishna concert special and his recent performance at the MS Subbulakshmi Auditorium of the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai did not fail to disappoint the audience in this regard. To date, Krishna is the only Carnatic musician who has the ability to elicit opposite opinions from two music lovers, who may even be his die-hard fans. His experiments with format and mood may upset someone who is emotionally attached to a particular composition and may feel that the tinkering he does is inappropriate. While another person may simultaneously scream in delight at the effort and wonder how he manages to execute such moves with gusto and aesthetic sense.

Such is Krishna’s spontaneity that even the padams he often sings in his concerts sound different every time he hears them. The padams have been glorified not only for their musical nuances but also for the unmatched erudition he delivers in an intimate setting. The auditorium, acoustically designed for performances without any form of electrical amplification, enabled the audience to hear even the subtle accompaniment that Krishna liberally improvised in the pallavi of the sringara padam ‘Yarukagilam’, a symbol of rebellion. His demonstration of nearly half a dozen ways of ending the phrase ‘pene’ enthralled the audience.

One of Arun Prakash’s significant contributions to this arrangement is undoubtedly his ingenious Arudis; here he rounded off the Anupallavi and connected it carefully to the Charanam. The Charanam ended with the phrase ‘Kasugusena’ in the upper Gandharaam. At this point a cycle of swaras was presented by Krishna, a set of whirlwind phrases that touched the lower and upper Gandharams in a wild manner. Just when one thought this was not enough of a diversion, Krishna chose to explore the Mandra Sthayi with a cycle of swaras on ‘Enna’ in the Pallavi. It must be said that this was a clever choice to use the setting effectively as the auditorium facilitated clear hearing of even the lowest Mandra Sthayi phrases.

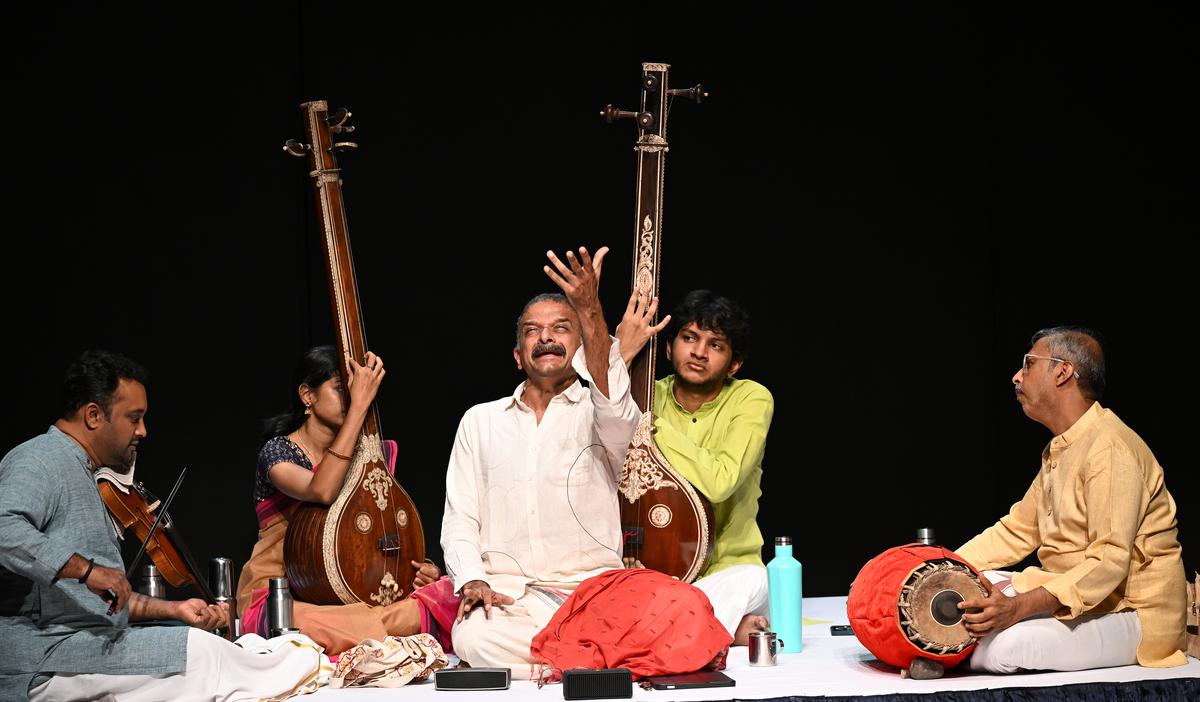

Krishna with Arun Prakash on the mridangam and HN Bhaskar on the violin | Photo courtesy: M. Srinath

One of the compositions that Krishna chose to perform was ‘Shubh Sukh Chain’, a Hindustani translation of Rabindranath Tagore’s poem ‘Bharato Bhagyo Bidhata’, the first verse of which is used as the national anthem. Rewritten by Subhas Chandra Bose with the help of writer Mumtaz Hussain and Colonel Abid Hassan Safrani, the song is a reimagining of the national anthem and makes significant changes from the original text and tune. Krishna mentioned that he decided to perform this composition because some verses in it echo his views on nationalism.

Possibility is what Krishna has shown the Carnatic music world right from the beginning. Take for example his analysis of Surutti Nishadam. Without going into many of its standard phrases, he chose to demonstrate how much the middle to upper Nishad section can be used to get the best out of the raga. Next, he added Shadjam to the Pancham layer, later moving on to reach Nishad from the upper Rishabham.

HN Bhaskar embarked on a similar expedition to explore the potential of ‘Nee’ in Surutti when Krishna intervened to include Kaakali Nishadam in the Alapana to make it a soulful desh. However, eventually, Kaishiki Nishadam gained supremacy and fought itself back to become a Vrindavan Saranga. Muthuswami Dikshitar’s ‘Soundararajam’ was rendered at a brisk pace leading up to the Thani. Arun Prakash provided an uninterrupted flow of gentle strokes throughout the composition and his Thani was a direct extension of this refined approach. Some were even bold enough to ask if what they heard was ‘Soundararajam’ in the midst of that continuous mridangam flow – such was Arun’s melodious presence that evening.

Krishna performed Michaels Concert at Asian College of Journalism. | Photo Credit: M. Srinath M

Renowned poet Perumal Murugan’s poems on birds are full of beautiful imagery and interesting alliteration. His fascination with the Indian Roller, known in Tamil as ‘Panangadai’, resulted in his reading the works of world-renowned ornithologist M. Krishnan. Murugan was particularly concerned that the Roller lives in solitude and hardly makes any noise. This composition by Krishnan in Khamas uses some of the typical phrases associated with Kakali Nishadam to highlight the unique characteristics of the bird in the lines ‘Neela Neera Rakkaiyai Seerakka Virithu Selumbodhu’ and ‘Porambai Padakkendru Paayum’. He talks about the bright blue markings on its wings

On asking Bhaskar to take the alapana, Krishna observed that the violinist played a clear Mayamalavagowla alapana. During his turn, Krishna cleverly removed the Daivatham and turned it into Jaganmohini and completed the section with superfast one-note notes for ‘Sobillu saptaswara’.

Many in the audience were happy to hear him sing ‘Bhare Panduranga’ and felt that the song was apt after Ashadhi Ekadasi. While presenting ‘Koluvamaregada’ in Todi, Krishna’s Neraval in ‘Tambura Jekoni’ was punctuated by meaningful pauses, where the harmonious sound of the two tambourines on stage further enhanced the mood of the sahitya.

Krishan will always remain the musician who taught an entire generation how to free art from stereotypes. All we need to do is resolve to let different forms of artistic expression co-exist in harmony, without one dominating the other.